Adapted by Denise Cummings-Clay

Conditions of Use:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Chapters derived from:

https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/music-and-the-child

by Natalie Sarrazin

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License.

Click on the printer icon at the bottom of the screen

![]()

Make sure that your printout includes all content from the page. If it doesn't, try opening this guide in a different browser and printing from there (sometimes Internet Explorer works better, sometimes Chrome, sometimes Firefox, etc.).

If the above process produces printouts with errors or overlapping text or images, try this method:

Chapter Summary: This chapter introduces the reader to processes and vocabulary of music integration, including a general definition of arts integration, and strategies and examples for integrating music with other subject areas.

Musical training is a more potent instrument than any other, because rhythm and harmony find their way into the inward places of the soul.

—Plato, Republic, Book III

Arts Integration, when done correctly, transforms both the art and the subject area into a whole greater than the sum of its parts. In short, Arts Integration can be magical, inspiring learning and setting off a spark in each child. Imagine the difference in a child’s learning experience if classroom teachers incorporated the arts into their lesson. From a teaching perspective, artistic experiences help teachers discover their students’ enthusiasm through a new medium. They also aid in creating positive and interesting lessons that fully engage the student. For the student, music not only strengthens emotional and cognitive development, but also allows a new outlet of expression, and a new means of learning through listening and making sound. The arts provide a platform through which teachers can tap into a child’s creativity and humanity while teaching content material. The arts give students an opportunity to express and explore material in a medium to which they might not otherwise have access.

Incorporating music is beneficial to both teacher and student as it strengthens the bond between them through a (hopefully) mutually satisfying aesthetic experience. Teaching and learning occurs between the art forms and any number of diverse subject areas.

Let’s begin with a commonly accepted definition of arts integration from the Kennedy Center’s ArtsEdge website along with a checklist to help guide the teacher in the creation of an integrated lesson.

“What is Arts Integration?” Courtesy of ArtsEdge, by Lynne Silverstein and Sean Layne. © The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

A definition of arts integration

“Arts Integration Checklist” Courtesy of ArtsEdge, by Lynne Silverstein and Sean Layne. © The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

Approach to Teaching |

|

Understanding |

|

Art Form |

|

Creative Process |

|

|

Connects |

|

|

Evolving Objectives |

|

|

Not all lessons that use the arts can be called “integrated.” Some lessons incorporate the arts, but do not incorporate the learning objectives and other criteria that fully integrate them, while others follow a deeper level of integration. Silverstein & Layne (2014) identify 3 categories of Arts Integration:

There is nothing wrong about any of these three ways of using the arts, and sometimes it is quite appropriate to use one style over another for various curricular or other reasons. Although integration is a worthy goal, it is sometimes not feasible.

Most schools still contain music and art teachers, who are valuable assets in providing input regarding art strategies, teaching materials, etc. This is definition of an arts-as-curriculum strategy, where the arts teacher teaches their separate material. Fully integrating the arts requires a time commitment and instructional expertise, but often there isn’t the time, resources, or incentive to fully learn or implement the entire process for a lesson. How might you utilize the music teacher in your school to enhance your lesson? What are some ways to work with the specialists to benefit the student’s learning experience?

There are many things to be learned from arts-enhancement as well. Using the arts yourself to enhance your lesson provides opportunities for students to experience music during the school day in a non-content related way.

There are ample opportunities for children to experience music in their day, including singing, moving, clapping, or stomping that are not directly related to teaching content area but provide students an alternate form of expression, a chance to re-group and focus, for motivation, learn about proper group and individual expectations and behavior, and to make transitions between subjects and activities. How might you use music to “enhance” a science or language arts lesson? Vocabulary or poetry lesson?

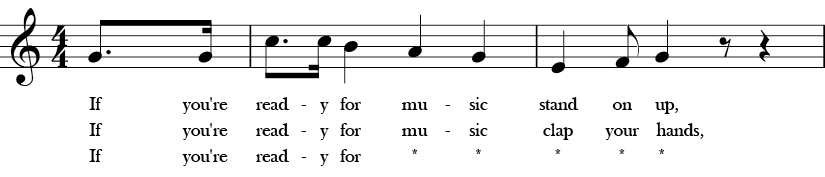

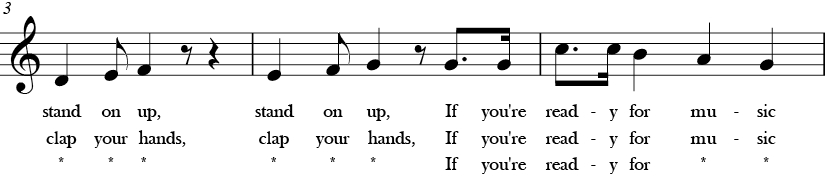

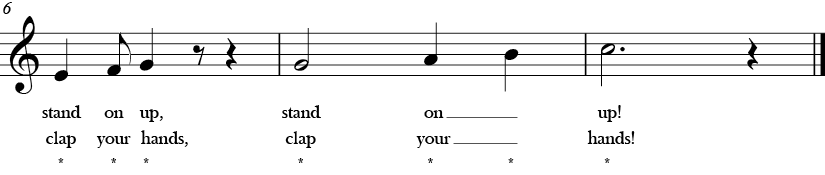

(Substitute any subject such as math, reading, physical education, art, instead of music, and any action instead of “stand on up” or “clap your hands.”)

Janet Elder, in her article on “Brain Friendly Music in the Classroom” (n.d.), suggests the following reasons to incorporate music into the classroom:

Reasons for using music in the classroom can be divided into four groups:

For example, as mentioned in Chapter 11, music’s beats per minute (b.p.m.) or tempo, has a direct impact on the human body.

Elder also goes on to suggest specific songs to use for different classroom situations, such as playing classical music during individual or group work or “Get Up Offa That Thing” by James Brown for stretch breaks. There are many, many different types of songs and places to use them when working with children, and the inclusion of music in the daily routine can improve transitions and the overall mood of a classroom.

Source: adapted from Elder (n.d.) “Using Brain-Friendly Music in the Classroom”

Class Activity |

Musical qualities to look for in song selection |

Song examples |

|

As students enter class. |

Select loose, upbeat, uplifting music, or music that pertains in some way to the course or topic that day. Songs with humor also start the class on the right foot. |

“Star Wars,” “Summon the Heroes” and other John Williams’ Olympic music, “Walk Right In” (Rooftop Singers), “Thanks for Coming” and “Hello, Welcome to the Meeting” (“Laughable Lyrics” CD), and “The More We Get Together” (Raffi). |

|

To welcome students back after a weekend or holiday break |

“Hi-Ho, Hi-Ho, It’s Off to Work We Go!”, “The Flintstones” (“Yabba Dabba Do” TV theme, Aron Apping), “Monday, Monday” (Mamas and Papas), “Reveille” bugle call (“Authentic Sound Effects, Vol. 3”). |

|

|

To comment on the weather. |

On a rainy day:

For sunny days:

|

|

|

To get students on their feet. |

Students need a change after 15-20 minutes of sitting. Use any of these when you want to have them stand up to stretch, change where they are sitting, or move for some other reason. |

“Get on Your Feet” (Gloria Estefan), “Line Up” (Aerosmith), “Stand Up!” (David Lee Roth), “1-2-3-4” (Ataris), “Up!” (Shania Twain), “Get Up Offa That Thing” (James Brown),“Arkansas Traveler” (“Smokey Mountain Hits” CD) |

|

As students are moving into collaborative groups. |

Look for songs with themes of friends, help, or general encouragement. |

“Help,” (Beatles), “We Can Work It Out,” (Beatles), “You’ve Got a Friend” (Carol King), “Lean on Me” (Bill Withers), “Reach Out” (The Four Tops), “I’m into Something Good” (Herman’s Hermits), “Call Me” (Blondie), “You Can Make It if You Try” (James Brown). |

|

After a pair-share review (Students make the immediate connection between these songs and having to recall/review material) |

Select songs with titles or lyrics that include “remember,” “memory,”etc. |

“Thanks for the Memories” (Bob Hope and Shirley Ross), “Always Something There to Remind Me” (Naked Eyes), “Unforgettable” (Peggy Lee) |

|

As low background music when students are working in small groups, in pairs, or individually, or when they are taking a test. |

The volume should be low enough that you could speak at a conversational level without raising your voice. The music should act as a filter for unwanted noise and help create a relaxed, mentally alert state. If any student objects to background music, you should not use it. However, if the entire class likes background music, try to play the same baroque music during the test that was used during the original presentation of the material: it acts as an auditory memory cue. |

“Water Music Suite” (Handel), “Brandenberg Concertos” (Bach), “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” (Mozart), and music by Telemann, Vivaldi, or Corelli in a major key. Soft piano or violin concertos with orchestral accompaniments work well. |

|

To use music to create positive stress or add drama |

“James Bond Suite” (Henry Rabinowitz and the RCA Orchestra), “Law and Order” (TV theme), “Jeopardy” (TV theme); “Mission Impossible” (TV theme); “Jaws” (movie theme, John Williams), “In the Hall of the Mountain King” (from “Peer Gynt” by Grieg) |

|

|

To energize students or have them physically move: |

Select highly rhythmic music in a major key or any upbeat music or song. Beats per minute should be 70-140. |

“Shake It Up” (The Cars), “Fun, Fun, Fun” (Beach Boys), “Bonanza” (TV theme), “Listen to the Music” (Doobie Brothers), “We Got the Beat” (Go-Gos), |

|

To relax or calm students, to use for stretching, or activities such as reflection, journaling, and visualization. |

Beats per minute should be 40-60. |

“The Lake House” (movie theme; Rachel Portman), “Chariots of Fire” (Vangelis), “The Reivers” (movie theme), “Peaceful, Easy Feeling” (Eagles); |

|

To celebrate successes or to honor students. |

“Olympic Fanfare” (John Williams), “In the Zone” (David Banner), “I Just Want to Celebrate” (Rare Earth), “Celebrate” (Three Dog Night), “Celebration” (Kool and the Gang), “We Are the Champions” (Queen). |

|

|

To end class: |

Select upbeat, fun, or funny music; lyrics may pertain to leaving. |

“Never Can Say Goodbye” (Gloria Gaynor), “So Long, Farewell” (from “The Sound of Music”), “Who Let the Dogs Out” (Baja Men), “Happy Trails” (Roy Rogers/Dale Evans). |

|

For other purposes. Beginning of class Encouragement, motivation, support: Funny, and therefore stress-reducing |

An arts integrated lesson plan will be similar to a regular lesson plan, with the exception that it will have a place for both the arts learning objectives as well as the objectives for the content area, and will allow students the opportunity to construct understanding through both disciplines.

Consider that you have to create a lesson plan to celebrate the Martin Luther King, Jr. holiday. It is, of course, nice to add a song somewhere in the lesson, perhaps a song from the Civil Rights Movement. This does not make the lesson integrated, but rather an Arts-Enhanced-Curriculum as discussed above. Integration requires that there be music objectives as well as subject area objectives, and that both subjects are treated equally. Keep in mind that any lesson can be made into an arts-integrated one, by simply delving in deeper to the art form itself to find structural details and meaning from which to draw. To make a lesson integrated, it is necessary to include social science or history goals and objectives as well as musical information, goals and objectives. For example, including information about the song that incorporates the music itself (form, timbre, melody, rhythm, etc.), while discussing the genre of civil rights songs itself.

To demonstrate a deeper understanding of the tenets and issues of Civil Rights, social science connections can be made not only to slavery in the previous century, but to the pro-union struggle in the earlier part of the 20th century. Students could demonstrate their understanding of Martin Luther King’s leadership and the famous marches of the 60s through song by recreating the march on Washington, DC while singing a civil rights song (“We Shall Not be Moved,” “This Little Light of Mine,” “We Shall Overcome,” etc.)The types of songs used for demonstrations could be analyzed, including their roots in the pro-union movement, gospel and religious music, and/or the use of call and response in the songs, which dates back to slavery and early African-American culture, and particularly how music was used during the protests. A follow-up might focus on blues, jazz and other genres inspired by the music of the Civil Rights movement.

|

Activity 12A Try this Which one of these examples represents Arts as Curriculum, Arts-Enhanced Curriculum, and an Arts-Integrated Curriculum?

Now try this

|

In order to successfully create arts integrated lessons, begin with the state learning standards in the content area in which you are working, then consider the art form you will be using. Explore vocabulary that may help you to work between the two disciplines. Below are two examples of vocabulary lists from Education Closet, a website dedicated to integration and innovation in teaching.

|

Activity 12B Try This Review the vocabulary lists below. Identify which terms work best for music instruction. Select three of the terms from either list and give an example of how you might use that term to illustrate music concepts in addition to either a math or literacy concept. |

Source: Susan Riley, Education Closet

|

Grade |

Shared Vocabulary between Literacy and the Arts |

K |

Illustrations, illustrator, listen, setting, space, title, beginning, end. |

1 |

Audience, character, collaborate, connections, expression, fluent, phrase, plot, segment, sequence. |

2 |

Analyze, compare, contrast, expression, genre, introduction, point of view, rhythm. |

3 |

Audience, comparative, dialogue, effect, line, mood, narrator, plot, point of view, scene, stanza, theme. |

4 |

Animations, categorize, drama, elements, meter, narration, pose, stage direction, theme, verse. |

5 |

Analyze, compare, conclude, contrast, dialect, dialogue, evaluate, expression, fluent, influence, interpret, mood, multimedia, perspective, perspective, reflection, theme, tone, voice. |

6 |

Bias, convey, elaborate, interpret, multimedia, perceive, point of view. |

7 |

Alternate, analyze, audience, categorize, collaborate, composition, concept, embellish, exposure, format, function, interact, medium, mood, segment, structure, tone, unique. |

8 |

Analyze, bias, characterization, elaborate, evaluate, imagery, point of view, style, symbolism, theme. |

9 and 10 |

Bias, coherence, clarity, comedy, character motivation, diction, dynamic, monologue, mood, plot structure, purpose, soliloquy, theme, tone, tragedy, digital media, quality. |

11 and 12 |

Context, diction, digital media, nuance, perspective, satire, structure, style, subplot, subtle, theme, voice. |

Source: Susan Riley, Education Closet

|

Grade |

Shared Vocabulary between Literacy and the Arts |

K |

Compare, opposite, before, different, similar, object, measure, pattern, curves, slide. |

1 |

Similar, object, symbol, group, pattern, compare, half, describe, side, size, parallel, curves, slide, turn. |

2 |

Form, sequence, pattern, group, interpret, symbol, slide, reflect, turn, measure, three-dimensional, line of symmetry, intersect. |

3 |

Expression, form, product, length, symbol, combinations, weight, angle, symmetry, line, dimensions. |

4 |

Comparison, expression, produce, symmetry, measure, length, interpret, frequency, distance, lines. |

5 |

Patterns, form, expression, variation, inverse, sequence, symbol, product, ratio, part, whole, quarter, half, organize, arrange, scale, line, distance, vertical, diagonal, horizontal, symmetry, transformation. |

6 |

Scale, measure, compose, symbol, expression, grid, collection, interval, simulation, symmetry. |

7 |

Point, area, proportion, analyze, compose, notation, expression, value, range, scale, drawings. |

8 |

Expression, value, notation, frequency, non-linear, rigid, symmetry. |

9 and 10 |

Expression, notation, properties, model, measure, acceleration, scale, direction, structure, value, range, vary, inverse, frequency. |

11 and 12 |

Linear, range, oblique, measure, symmetry, composition, variation, velocity, arc, chord. |

The following grid offers a process for generating integration ideas using music, particularly in making connections across the disciplines. The first row of the grid contains an example of how to generate ideas from a musical concept.

Begin by selecting one music concept to work with. In the first column of the grid below, the word “staff” is written. The lesson is to teach the musical staff to 2nd grade students.

What are your main objectives for the lesson? What should children be able to do by the end of the lesson that they couldn’t do at the beginning? Note: “SWBAT” stands for “Students Will Be Able To.”

What activities could you use to teach the staff? Where would you begin? You might begin by teaching the line and space notes for the treble staff (EGBDF and FACE), and teaching the mnemonics that accompany those note names (i.e. E-Every; G-Good; B-Boy; D-Deserves; F-Fudge). Even at this point, writing the lines on the board, on a smart board, PPT, or even making lines on the floor with tape can be a visual accompaniment to the lesson, and help students learn through body movement as well as visual learning.

How might you integrate this concept using different core subject areas? What higher order thinking skills, or vocabulary? Look at the second grade Vocabulary grid above from Education Closet concerning math and the arts and Music and Literacy and select the most appropriate terms to apply to the lesson:

Now refer to the earlier chapter in the book to find the appropriate common core learning standards for the lesson.

Music ConceptGrade |

Objectives |

Activities |

Integration (connections, constructivism, creative process, understanding) |

Learner/Common Core Standard |

|

Ex. Concept: Reading the Music Staff Grade: 2nd |

SWBAT identify pitches on lines of the treble staff SWBAT analyze the correlation of skipping and sequential regarding the pitches on the treble staff. SWBAT understand correlations across disciplines of math, literacy and music between sequential movement and skipping movement |

Review (or teach) the pitches of the treble staff, first using sequential alphabet letters, then using the acronyms EGBDF, and FACE. Create huge lines of treble staff on the floor using masking tape. Mark each line or space with large letters for each note. Movement: Have students physically move across the floor staff, first sequentially and then skipping line to line and space to space, reciting the letters as they go. |

Literacy: Analyze the letters EGBDF as a mnemonic for “Every Good Boy Deserve Fudge.” Brainstorm, having students create their own acronyms for EGBDF and FACE. Compare and contrast the pitch names on the staff with the letters of the alphabet. Which direction do they go? What are the differences between letters of the alphabet and music pitch names? Math: Discuss the form of the staff. Is there a pattern? What is it? Does it alternate (skip)? Is it sequential (all in a row)? Math, Music and Literacy: (EGBDF) . Have students count sequentially. Sequence the letter names by saying them in a row (EFGABC). Then create a pattern by skipping every other letter of the alphabet (B – D – F or A – C – E). Then correlate with math by switching to numbers. Practice grouping by 2s. |

Bodily-Kinesthetic, Visual-spatial/Creating, Performing, Participating |

|

1. Concept: Rhythm: Eighth and Quarter notes Grade: Kindergarten |

||||

|

2. Melody: Pitch Grade: 4th |

||||

|

3. Timbre: Voice Grade: 1st |

Music ConceptGrade |

Activities |

Integration (connections, constructivism, creative process, understanding) |

Learner/Common Core Standard |

Objectives |

|

1. |

||||

|

2. |

||||

|

3. |

(see also “Erie Canal” Lesson Plan in Chapter 6)

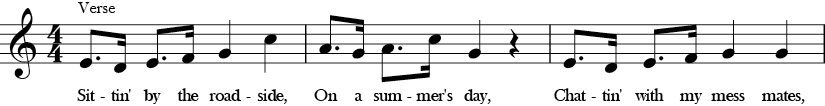

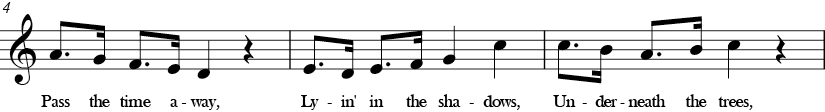

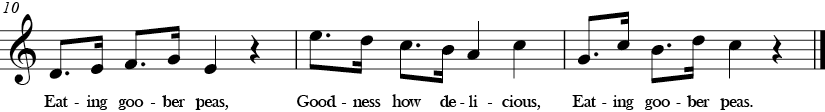

Many older songs offer excellent material for integration. For example, the song “Goober Peas” provides students a very inside look at the life of a Confederate soldier during the Civil War. In this case, both the music and lyrics are highly informative, as is the situation in which the song was sung, lending itself to integration through three areas: music, language arts and social sciences.

Timeline: Civil War history timeline including various battles, Sherman’s March, etc.

Song: “Goober Peas”

Text: The Personal Story of Life as a Confederate Soldier, “The Letters of Eli Landers” http://www.gacivilwar.org/story/the-personal-story-of-life-as-a-confederate-soldier

Southern U.S. folk song, 1866

Sung by Confederate soldiers during the Civil War

2. When a horse-man passes, the soldiers have a rule

To cry out their loudest, “Mister here’s your mule!”

But another custom, enchanting-er than these,

Is wearing out your grinders, eating goober peas. (refrain)

3. Just before the battle, the General hears a row

He says, “The Yanks are coming, I hear their rifles now”

He turns around in wonder and what d’ya think he sees?

The Georgia militia, eating goober peas. (refrain)

4. I think my song has lasted almost long enough

The subject’s interesting but the rhymes are mighty tough

I wish the war was over so free from rags and fleas

We’d kiss our wives and sweethearts and gooble goober peas. (refrain)

How might you integrate this song beyond that of “Arts as Enhancement”? What learning principles will you use? How will students be engaged? Demonstrate their understanding? What will be the processes of creation? What connections to other parts of the curriculum can be made? Are the standards present for both the art and the subject? Go through Silverstein & Layne’s Arts Integration checklist below to see how to incorporate an integrated level of understanding to the lesson.

You’ll find an abundance of material to integrate and connect after analyzing both the music, lyrical/poetic aspects, and social contexts. The musical forms, phrases, harmonies and the poetic structure reveal a great deal of material apart from the content of the lyrics.

|

Music |

Poetry/Lyrics |

|

|

Setting: Civil War, soldiers resting on the roadside while waiting for orders for the next confrontation.

Date Written: 1866.

Singers: Popular in the South among Confederate Soldiers (losing the war).

Sentiment: Expresses the living conditions of Confederate soldiers and the public, as the war was lost. Sherman’s troops laid waste to much of Georgia, cutting off food supplies.

Students may not be familiar with these terms:

Goober Peas—another name for boiled peanuts. Eaten by Confederate soldiers during the war when rail lines were cut off, making food and rations scarce.

Messmate—a person/friend in a military camp with which one regularly takes meals.

Grinders—teeth.

Row—an argument or fight (rhymes with “cow”).

Georgia Militia—a militia organized under the British that fought the Union during the Civil War. They fought in Sherman’s devastating “March to the Sea” and in the last battle of the Civil War at the Battle of Columbus on the Georgia-Alabama border.

Yanks—Refers to “Yankees” or Union soldiers of the North.

Rags and fleas—Tattered clothing and poor health conditions.

Sing the song “Goober Peas;” Read some of the letters of Eli Landers.

What Learning Standards or Objectives can you incorporate for this lesson for each of the following?

a. Language Arts 3: Use knowledge of language and its conventions when speaking, reading, or listening.

b. Writing 3: Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, descriptive details, and clear event sequences.

c. Reading 2: Determine a theme of a story, drama, or poem from details in the text; summarize the text.

a. 1: Singing, alone and with others, a varied repertoire of music.

b. 6: Listening to, analyzing, and describing music.

c. 8: Understanding relationships between music, the other arts, and disciplines outside the arts.

(see also “Erie Canal” Lesson Plan in Chapter 6)

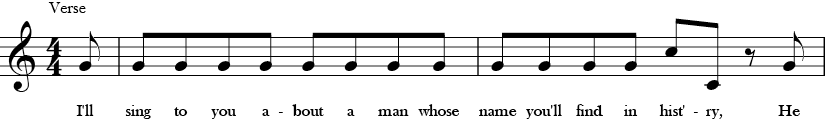

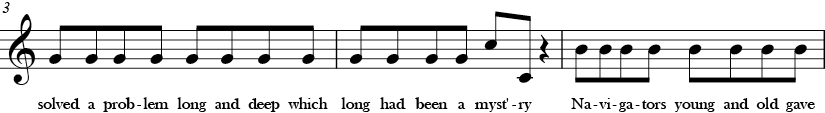

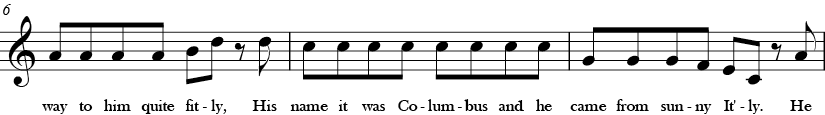

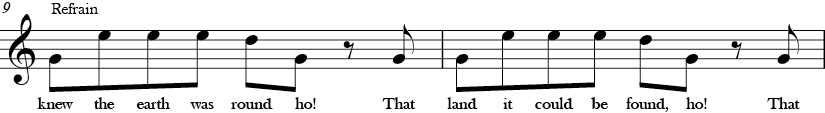

Other examples include songs that are informative and contain a long narrative or historical information for students. For example, the song “Christofo Columbo” chronicles much of the famed voyage including detailed geographic references in a fun and light song.

Ring Lardner, 1911

To the Kings and Queens of Europe, Columbus told his theory,

They simply thought him crazy, and asked him this here query,

How could the earth stand up if round, it surely would suspend,

For answer, C’lumbus took an egg and stood it on its end.

Refrain

In Fourteen Hundred and Ninety-two, ’twas then Columbus started,

From Pales on the coast of Spain to the westward he departed,

His object was to find a route, a short one to East India,

Columbus wore no whiskers, and the wind it blew quite windy.

Refrain

When Sixty days away from land, upon the broad Atlantic,

The sailors they went on a strike which nearly caused a panic,

They all demanded eggs to eat for each man in the crew,

Columbus had no eggs aboard, but he made the ship lay too.

Refrain

The hungry crew impatient grew, and beef-steak they demanded,

Equal to the emergency, Columbus then commanded

That ev’ry sailor who proves true, and his duty never shirks,

Can have a juicy porterhouse, “I’ll get it from the bulwarks.”

Refrain

Not satisfied with steak and eggs, the crew they yelled for chicken,

Columbus seemed at a loss for once, and the plot it seemed to thicken,

The men threatened to jump overboard, Columbus blocked their pathway,

And cried: “If chicken you must have, I’ll get it from the hatchway.”

Refrain

The sailors now so long from home with fear became imbued,

On the twelfth day of October their fears were all subdued,

For after Ninety days at sea, they discovered America’s shores,

And quickly made a landing on the Isle of Salvador.

Refrain

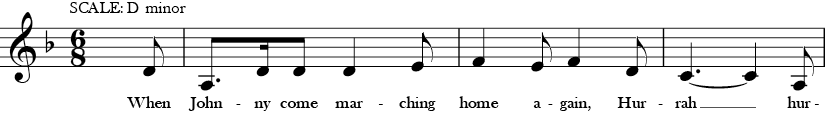

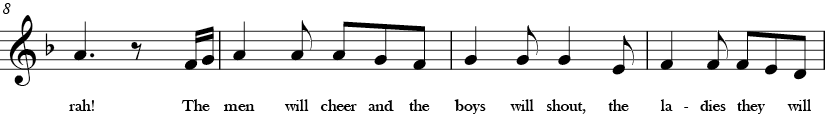

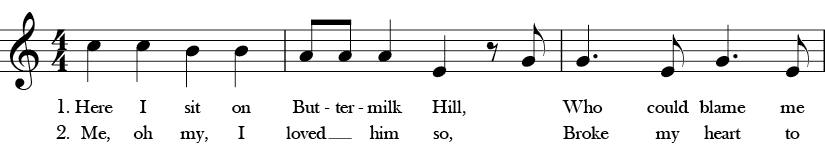

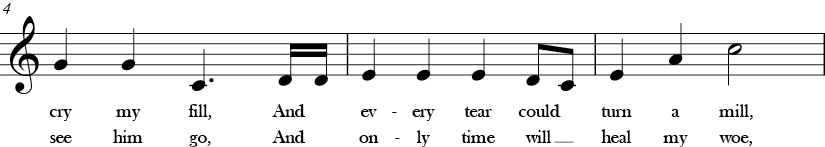

Patrick Gilmore, 1863

American Civil War song

Traditional English folk song popular during the Revolutionary War

Of all of the content area relationships with music, language arts and music have one of the closest bonds. This bond is rooted within the inseparable relationship between lyrics and music that has existed for thousands of years. People in across countless cultures have chanted or sung poetry for all types of human rituals, ceremonies and for entertainment. When we listen to a song, a musical phrase usually accompanies a phrase of lyrics; a verse or refrain emerges from a short poem. For centuries, ballads, and epics were all sung, as were Biblical chants and Vedic hymns. Long stories and epic tales used music to draw in the audience and to help the reciter’s memorization.

In addition, there is an intrinsic relationship in the discrimination of phonemic sounds and musical sounds for children learning to read. Language and music are intertwined to the point where there is evidence of a connection in the brain between phonemic sound discrimination and musical sound discrimination. In a 1993 study, for example, Lamb and Gregory examined the correlation between phonemic and musical sound discrimination for children reading in their first year of school, and discovered that a child’s ability to discriminate musical sounds is directly related to reading performance, primarily due to their awareness of changes in pitch.

This close relationship allows for multiple avenues for integration. The use of music to build characters through sound expression; create tension in the narrative; highlight important moments in the plot, and so forth, are examples of the high compatibility between words and music.

Since music and language have such a close relationship, one of the easiest ways to begin is to combine the two. Creating a sound carpet entails taking a story and adding sound effects, leitmotifs, instruments, vocal sounds, body percussion, and actors and/or a narrator, in order to bring literature to life. The goal of a leitmotif is to help the listener identify the main characters and give each a very short musical pattern, so that every time their name is mentioned, someone plays that pattern. Also, sound effects can be added to enhance the action or bring a fuller meaning or experience. For example, if the story introduces a chiming bell, hit a bell or, for more advanced or older students, play a bell peal on the glockenspiel. Folk tales and fairy tales from around the world are excellent sources for this type of activity

To create a sound carpet, begin by making a list of the main characters in the story. For example, the story The Princess and the Frog has three main characters—the King, Princess and Frog. Sample leitmotifs might look like this:

King: (temple blocks and bass xylophone) q ioq q

Princess: (glissando on glockenspiels)

Frog: scrape guiro; hit hand drums q q q (say “ribbit!”)

Help students create a short phrase or leitmotif for each of the main characters—think of Star Wars’ Darth Vader theme as an example. Every time the name is introduced in the story, their leitmotif should be played. To help the creative process, you might give students a short, simple rhythm to work with to create the motif. Then play the leitmotif on an instrument that helps describe that character. The King’s leitmotif, for example, might be 4 quarter notes played on a trumpet sound on a keyboard, or using an interval of a 5th on any instrument to sound regal and stately.

Next identify locations in the story where sound effects can be used. A running stream could be a glissando on a xylophone; thunder can be played with drums; footsteps with a woodblock, etc.

Then add body percussion (clapping, stomping) or vocal sounds (moans for wind, yells and whoops) to increase the creativity and excitement level in the story.

Add a short song whose lyrics are based on the story, to be sung and played by everyone at the opening and closing of the story.

Finally, assign a narrator, speaking or acting parts, and along with your instruments and sound effects, you have a complete performance that incorporates music composition and creativity along with language arts and theater.

Appel, M. (2006). Arts Integration across the Curriculum. Leadership, Nov/Dec., 14-17.

Burnaford, G., Aprill, A., & Weiss, C. (Eds.). (2001). Renaissance in the classroom: Arts integration and meaningful Learning. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates.

Elder, J. (n.d.) Brain-friendly music in the classroom. www.thereadingprof.com retrieved from: https://letsgetengaged.wikispaces.com/file/view/Music.pdf

Goldbert, M,. & Bossenmeyer, M. (1998). Shifting the role of arts in education. Principal. 77, 56-58.

Gullatt, D. (2008). Enhancing student learning through arts integration: implications for the profession. The High School Journal, 85,12-24.

Ingram, D., & Riedel, E. (2003). What does arts integration do for students? (CAREI Research Reports). Minneapolis, MN: Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement. Retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, http://purl.umn.edu/144121

Ingram, D., & Meath, M. (2007). Arts for academic achievement: A compilation of evaluation findings from 2004-2006. Minneapolis, MN: Center for Applied Research and Educational Improvement. Retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, http://purl.umn.edu/143647

Jenson, E. (2002). Teach the arts for reasons beyond the research. The Education Digest, 67(6), 47-53.

Koutsoupidou, T., & D. J. , Hargreaves. (2009). An experimental study of the effects of improvisation on the development of children’s creative thinking in music. Psychology of Music, 3, 251.

Luftig, R. (2000). An investigation of an arts infusion program on creative thinking, academic achievement, affective functioning, and arts appreciation of children at three grade levels. Studies in Art Educatio,: 208-227.

Mishook, J., & Kornhaber, M. (2006). Arts integration in an era of Accountability. Arts Education Policy Review, 107(4), 3-10.

Moore, D. (2013). Make art not the servant. Retrieved from http://educationcloset.com/2013/02/27/make-not-art-the-servant/.

Rabkin, N., & Redmons, R. (2006). The arts make a difference. Educational Leadership, 63(5), 60-64.

Riley, S. (2012). Shake the sketch: An arts integration workbook. Westminster, MD: Author.

Ruppert, S. (2006). Critical evidence—How the arts benefit student achievement. National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. Retrieved from http://www.nasaa-arts.org/Research/Key-Topics/Arts-Education/critical-evidence.pdf.

Silverstein, L. & Layne, S. (2014). “What is Arts Integration?” ArtsEdge.Kennedy-Center.org. http://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/educators/how-to/arts-integration/what-is-arts-integration

Butzlaff, R. (2000). Can music be used to teach reading? Journal of Aesthetic Education, 167-178.

Cardany, A. (2013). Nursery rhymes in music and language literacy. General Music Today, 26(2), 30-36.

Carger, C. (2004). Art and literacy with bilingual children. Language Arts, 4, 283-292.

Darrow, A. A. (2008). Music and Literacy. General Music Today, 21(2), 32-34.

Fisher, D., McDonald, N, & Strickland, J. (2001). Early literacy development: A sound practice. General Music Today, 14(3), 15-20.

Lamb, S., & Gregory, A. (1993). The relationship between music and reading in beginning readers. Educational Psychology: An International Journal of Experimental Educational Psychology, 13(1), 9-27.

Snyder, S. (1994). Language, movement, and music—Process connections. General Music Today, 7(3).

arts integration: an approach to teaching in which students construct and demonstrate understanding through an art form. Students engage in a creative process, which connects an art form and another subject area and meets evolving objectives in both

leitmotif: a recurrent theme throughout a musical or literary composition, associated with a particular person, idea, or situation

sound carpet: extensive and liberal use of music, sound effects, and character leitmotifs in the performance of a narrative or story

trochee: in poetry, a trochee refers to a syllable pattern of stressed-unstressed, or long-short

Library Info and Research Help | reflibrarian@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4215

Loans or Fines | circ@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4222

475 Grand Concourse (A Building), Room 308, Bronx, NY 10451