Adapted by Denise Cummings-Clay

Conditions of Use:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Chapters derived from:

https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/music-and-the-child

by Natalie Sarrazin

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License.

Click on the printer icon at the bottom of the screen

![]()

Make sure that your printout includes all content from the page. If it doesn't, try opening this guide in a different browser and printing from there (sometimes Internet Explorer works better, sometimes Chrome, sometimes Firefox, etc.).

If the above process produces printouts with errors or overlapping text or images, try this method:

Chapter Summary: Children are inherently musical. They respond to music and learn through music. Music expresses children’s identity and heritage, teaches them to belong to a culture, and develops their cognitive well-being and inner self-worth. As professional instructors, childcare workers, or students looking forward to a career working with children, we must continuously search for ways to tap into children’s natural reservoirs of enthusiasm for singing, moving, and experimenting with instruments. But how, you might ask? What music is appropriate for the children I’m working with? How can music help inspire a well-rounded child? How do I reach and teach children musically? Most importantly, perhaps, how can I incorporate music into a curriculum that marginalizes the arts?

Over the past several decades, educators, world leaders, and theorists have produced a slurry of manifestos, visions and statements on what education should look like in the 21st century. Organizations such as Partnership for 21st century Learning (http://www.p21.org/) and The Center for Public Education (CPE) suggest ways to teach such skills to prepare students for the challenges ahead (see the CPE’s executive summary on the topic). The results favor integrative and holistic approaches that support the ideals of what a skilled 21st century student should know.

In this book, we will explore a holistic, artistic, integrated, and forward-thinking 21st-century approach to understanding the developmental connections between music and children. Rather than teaching children about music, this book will guide professionals to work through music, harnessing the processes that underlie music learning, and outlining developmentally appropriate methods to understand the role of music in children’s lives through play, games, creativity, and movement. Additionally, in this book we will explore ways of applying music-making to benefit the whole child, i.e., socially, emotionally, physically, cognitively, and linguistically.

The life of the arts, far from being an interruption, a distraction in the life of the nation, is very close to the center of a nation’s purpose—and it is the test of the quality of a nation’s civilization.

—J. F. Kennedy, 1962

Kennedy’s famous words, now decades old, provided the nation with legitimacy and a vision for the arts and arts education that still resonates today. There is a plethora of evidence regarding the critical role that the arts play in children’s lives and learning. Organizations and researchers have produced countless studies on the arts’ effectiveness and ability to engage children cognitively, emotionally, physically, and artistically: in other words, on a holistic level.

According to the National Coalition for Core Arts Standards (NCCAS), however,

Children’s access to arts education as part of their core education continues to be uneven across our nation’s nearly fourteen thousand school districts. Some local education agencies currently offer a full, balanced education that includes rich and varied arts opportunities for their students. However, too many schools have succumbed to funding challenges or embraced a narrow focus on tested subjects, resulting in minimal, if any, arts experiences for the children they serve. (2013, p. 3)

One of the challenges facing teachers’ use of the arts concerns a curriculum encumbered by a need to “teach to the test,” both at the state and federal levels. This trend began in the 1990s with an educational reform movement that stressed teacher accountability. Measurements through testing became accepted and standardized under the No Child Left Behind Act (2001) and also under the new Common Core State Standards Initiative currently being implemented. National and state laws and a trend toward teaching and testing “core subjects” reshape social perceptions and create a permanent culture that continually marginalizes the arts in the curriculum. The result impacts teacher perceptions regarding the incorporation of the arts in their lessons as there is a sense that using the arts is somehow a diversion that will take away classroom time from what are considered more “worthy” subjects. The arts, however, can be used effectively to augment this method, motivating students and appealing to their innate artistry and humanity.

This book is intended to aid those who have little or no background in music, in order to increase their comfort in integrating music into the curriculum. The material will help guide educators in finding methods to incorporate music with other subjects in a way that is inherently beneficial to teachers and students rather than a hindrance.

This book takes a holistic approach to the study of music, drawing from diverse fields such as music education, ethnomusicology, sociology, and cognitive sciences. The book takes into account many different perspectives on a child’s development rather than approaching it by focusing on only one subject. The material in this book is inspired by an approach to holistic education, the goal of which is to lead children towards developing and inner sense of musical understanding and meaning through physical, cognitive, creative, emotional and socially developmental means.

According to the Holistic Education movement, it is essential that children learn about:

Holistic education first addresses the question of what it is that the child needs to learn, and places the arts and aesthetics as key elements in teaching the developing child. Similarly, the holistic educator places music and the arts in a central position in a child’s education, emphasizing the artistic and aesthetic experiences that only the arts can bring.

A holistic approach not only includes children’s cognitive development, but their musical environment and cultural influences. In that sense, the book will address how children use music outside of the classroom. How do children experience music when playing or in leisure time activities? How do children think about music? How are they innately musically creative?

As an extension, the book also touches on some multicultural aspects of music, and considers the broad role of music and its importance to humanity, thus avoiding an insular and myopic Western Cultural view of the musical child. How do people in other cultures view music? How do children of other cultures experience music?

A discussion of 21st-century skills provides an important opportunity to consider change in the current state of the curriculum, future societal needs, and the role of music and the arts. Changing economics and demographics require flexibility and adaptability. What skills will children need to obtain employment? How can children be prepared to contribute and compete in a complex society? How can educators and educational systems meet these needs?

Alarmed at the condition of American public education, various institutions such as the Kennedy Center, The Partnership for 21st-Century Skills, 21st-Century Schools and the Global Alliance for Transforming Education organized to identify particular areas of educational focus deemed crucial for future learning. Their results place a high emphasis placed on student autonomy and independent learning, problem solving, and creativity, all of which are fundamental aspects of the arts.

The central components listed above continue an educational philosophy begun hundreds of years ago that stresses experiential learning, child-centered over teacher-centered learning, and process over product. It is part of what we now see as a holistic, collaborative, and integrated approach to education that emphasizes the development of social skills and inner confidence in addition to learning the subject matter.

All children are musical—they are born musical, and are keenly aware of sounds around them. Let’s begin with a journey from the perspective of the child—a very young child at the beginning of life. What does the child experience? What does he or she hear? Inside the womb, the baby hears the mother’s heartbeat, the rushing sound of amniotic fluid and the mother’s voice. From outside, the baby hears language and music, mostly low sound waves from bass instruments and loud noises. Because the visual sense is not viable at this point, the auditory senses are primary, and hearing is the most keenly developed of all of the fetal senses. Hearing develops from about 19 to 26 weeks of the pregnancy when the inner ear matures, and babies respond to voices and classical music by turning towards it and relaxing. They respond to loud noises as well by kicking, and curl up and turn away from loud rock or pop music (birth.com.au, 2013).

Do children remember what they hear in the womb? Auditory neuroscientists say that children do remember what they hear in the womb. Children remember their mother’s voice, and even melodies.

Children are part of two overarching social categories—humankind in general, and the specific culture in which they are born. As humans, music is an innate part of our existence, as we all possess the physical mechanisms to make and process organized sound just as we do language. As music educator Edwin Gordon notes, “Music is not a language but processes for learning music and language are strikingly similar” (Gordon, 2012, p. 6). The brain is wired for music and language, a topic that will be discussed in Chapter 7.

Music making and artistic endeavors represent the heart of a culture, and are part of each culture’s core identity: not only what makes us human, but also what makes each group of us unique. In the U.S., unique genres of music that are part of our cultural fabric have developed over the centuries. The melting pot that is America has yielded brand new genres such as big band, jazz, blues, rock and roll, etc. Blends of European, Caribbean, and African-American people combined in a way like that of no other culture. In America, all of the music we currently know today is derived from the musical genres that came before us. All children are born into that musical environment and pick up the musical repertoire and vocabulary around them.

Because societies believe that children are the key to continuing the traditions of their cultural and musical heritage, there is usually a separate category of songs that teach children their cultural and musical history.

|

Activity 1A Think of some familiar children’s songs. How many can you think of? What were your favorite songs as a child? Did your songs have games or movement of some kind? What does society think about children’s songs? Are they considered important or trivial? Are they nurtured or shunned? |

After remembering some of your favorite children’s songs, you may come to understand their importance. If you ask a group of people in any age category to sing a song, more often than not, children’s songs are the only songs everyone can sing in their entirety from beginning to end. Why is that? One reason is that music and identity are closely related, and groups or cohorts of people listen to particular songs targeted toward their age group produced by the market-driven music business.

Another reason is that children’s songs are uniquely structured to make them easy to memorize while containing basic musical and cultural material; language and codes that we come to recognize in all of our songs. We tend to think of children’s songs as simple, and in some ways, they are in terms of lyrics, structure, and music. However, there is much more to them that that.

|

Activity 1B What are some of the attributes of children’s songs that make them so memorable? Develop a list of characteristics that make children’s songs so popular, unforgettable, and able to survive for generations. Think about the musical aspects as well as the lyrical aspects. Are there a lot of notes or very few? Is there a big range or small? Are there many words or a few? Are there big singing leaps and lots of difficult runs or none? |

The body or repertoire of children’s songs is extremely old. In fact, the oldest songs you probably know are children’s songs! This is because children’s songs often preserve the social and historical meaning of a culture and the identity of its people. Many of our most popular American children’s songs hail from centuries of ballads, hymns, popular and folk music of early New Englanders, Scottish, and English settlers inhabiting Appalachia, and African and European descendants. All of the songs are rife with musical, cultural, and historical significance.

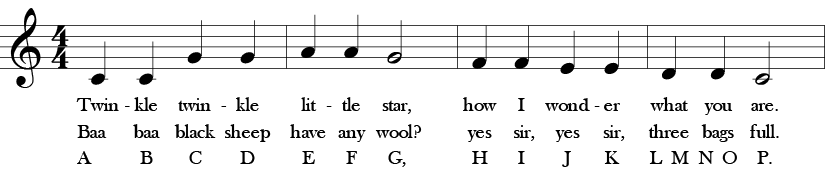

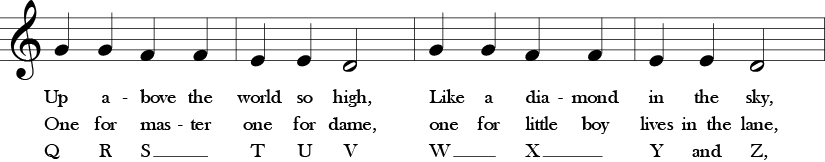

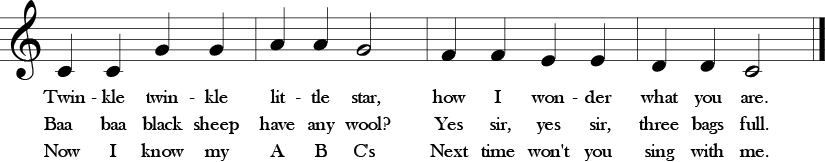

“Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” for example, is the product of both England and France, as an early 19th-century English poem set to an 18th-century French folk tune (“Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman”). The song also provides the music for two other very famous songs, “Baa, Baa Black Sheep” and the “A-B-C” song.

Melody: “Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman”

French folk song, 1761

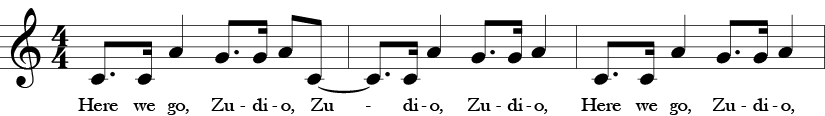

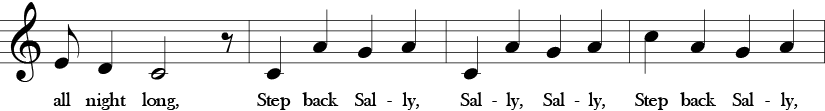

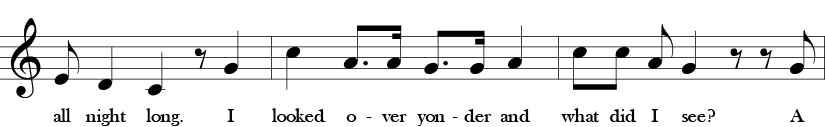

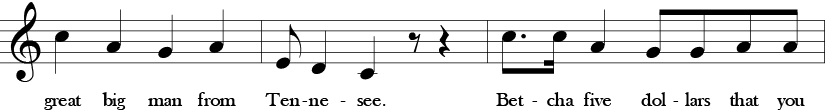

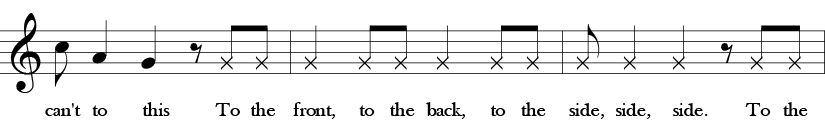

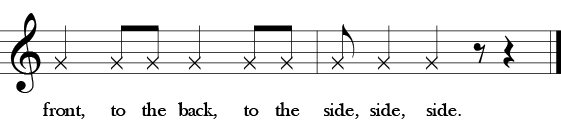

“Zudio” or “Zoodio” is an African-American children’s street game song with possible roots in slavery. It is suspected that the “great big man” mentioned in the song might be the slave owner.

African American song

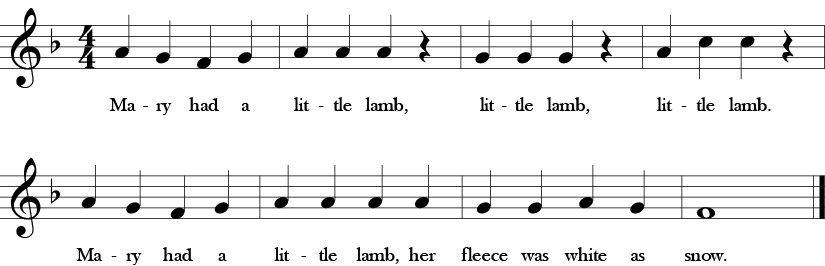

“Mary Had a Little Lamb” was inspired by a true incident in the small town of Sterling, Massachusetts, in the 1830s, when little Mary’s brother suggested that she take her pet lamb to school and chaos ensued. Below is a picture of the little schoolhouse where the incident of Mary and her lamb is believed to have taken place.

All of these songs have musical characteristics particular to the genre from which they emerged. They have only a few notes, small vocal ranges, no fancy ornaments, and simple words. However, they also have significant social and historical meaning that helps to explain their incredible longevity in the children’s song repertoire.

Dudesleeper at English Wikipedia [GFDL], CC-BY-SA-3.0 or CC BY 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

The Redstone School, now located in Sudbury, Massachusetts, where Mary supposedly took her lamb!

To explore the idea of music as culture, let’s look further at Mary and her lamb. “Mary Had a Little Lamb” is an almost 200-year-old song that remains compelling and still very popular today. Part of the song’s popularity is the subject matter. It was inspired by the real-life actions of children, and did not emerge wholly from an adult’s imagination. The melody is very simple, containing only four pitches and a fair amount of repetition. The meaning of this song is historically significant. The lyrics retain images of early American life: the one-room schoolhouse, the rural environment, no industrial noise and automobiles, and the prevalence of animals. A child growing up on a farm surrounded by animals would naturally befriend some of them. The idea that the child, Mary, would want to bring her favorite animal to school is more than understandable, and is akin to wanting to bring our dog or cat to school with us today. In other words, the song relives and retells the experiences of a child in another century and makes her story highly relatable to us today.

|

Activity 1C THINK ABOUT IT How much do you know about your favorite children’s songs? Look up the background of some of your favorite children’s songs such as “Ring Around the Rosie” or “London Bridge.” |

[The purpose of music in the schools]…is to prepare students for full participation in the social, economic, political, and artistic life of their homeland and the world at large. (Blacking, 1985, p. 21)

This statement, from ethnomusicologist John Blacking, highlights the holistic nature and potential impact of the educational system. Schools, however, provide formal music education, which is just one of the sources of a child’s musical heritage. Often, the most important sources are informal. Children encounter music at home, in their everyday cultural environment, and while at play. All of these settings are part of a person’s enculturation, or learning one’s culture through experiences, observations, and both formal and informal settings.

At home, children are exposed to a family’s musical heritage, which may contain music unfamiliar to those in their dominant culture. Music expresses identity, and children often take part in family celebrations that represent an ethnic or religious heritage. They are exposed to the music of their parents and siblings, friends, and relatives, casting a wide net over multiple experiences and genres.

Culturally, children are exposed to entire repertoires of music, which represent different parts of the American identity. From commercial music—pop and rock to jazz, from folk songs to national songs, religious and holiday songs, and multicultural music—children hear the rhythms, melodies, and harmonies that make up their musical environment. They unconsciously absorb idioms (i.e., musical styles, genres, and characteristics), which will render certain sounds familiar to them and certain sounds “foreign” and unfamiliar. Thus, the music and all of its elements that children are exposed to become as familiar as their native language.

In elementary school, or any early formal educational setting, children often learn music from a music specialist with a set music curriculum and learning goals. This has both positive and negative consequences. On the positive side, children are learning from a professional, trained to teach music to children. On the negative side, arts teachers are seen as separate “specialists,” which erroneously relieves the classroom teacher of any responsibility for incorporating the arts into the daily classroom experience.

If you can walk you can dance; if you can talk you can sing.

—Zimbabwean Proverb

With restricted budgets and reductions in arts specialists in some school districts, access to the arts for many children relies solely on what the classroom teacher can provide. Unfortunately, many classroom teachers feel inadequately prepared to teach music, and classroom teachers’ use of music varies widely according to prior exposure to music. It has been shown that teachers with “higher levels of confidence in their musical ability indicate stronger levels of beliefs about the importance of music” (Kim, 2007, p. 12). Teachers with the ability to read music notation, for example, felt more positively about including music in their classroom, and were more likely to use music in their teaching.

The truth is that we all know a great deal about music through enculturation. Everyone is familiar with certain repertoires of music (national songs, children’s songs, popular songs, folk songs, and even classical pieces), and even the different elements of music (melody, harmony, rhythm, form, and timbre). The Zimbabwean proverb, “If you can walk, you can dance; if you can talk, you can sing,” is quite apropos here. By virtue of your everyday experiences with music, you know more than you think about music, and can probably easily answer the questions in Activity 1D.

Although these questions might seem to be simple, they reflect a depth of music knowledge garnered throughout a lifetime of cultural exposure to music. For example, the above questions cover music theory, analysis, repertoire, and the uses and function of music in culture. Believe it or not, your accrued, cultural knowledge, added to a little enthusiasm and singing, is more than enough to be able to incorporate music into a lesson or curriculum.

Most people believe that music plays a significant role in their lives. Just think about the amount of time you spend surrounded by music in your day. The role of music, however, has changed dramatically in recent years. For thousands of years, the only way to experience music was to make it. Trained musicians and amateurs made music that fulfilled a variety of functions as part of religious rituals, work, story-telling, social communication, and also entertainment (see Merriam and Gaston’s functions of music in Chapter 7). In traditional societies, music would normally be part of everyday work, worship, and leisure. Complex societies, however, separate music making and the music makers from everyone else, who become consumers or listeners. Technology has helped to alter the balance of the musical experience, favoring music listening over music making. Children now grow up spending much of their leisure time hearing music rather than performing or making it.

Currently, almost all of the music we experience is no longer live, but pre-recorded. Technology, however, has also increased the number of opportunities we have to hear music. Recordings have made music accessible everywhere: TV, radio, CDs, Internet, video games, personal music players, etc. Music is so ubiquitous that many people don’t even notice it anymore. What has not changed, however, is a child’s innate desire to be musical, make music, and learn from it. The music room and regular classroom are some of the only places many children have to make music in their day.

Activity 1D

TEST YOUR MUSICAL KNOWLEDGE

Complete the following:

a. Rhythm

b. Melody

c. Form

d. Tempo

_______________________________

a. Melody

b. Bass

c. Harmony

d. Timbre

_______________________________

a. Supported by other instruments (accompaniment)

b. The most dominant part of a song

c. Where the lyrics can be found

d. All of the above

_______________________________

a. Keeps the beat

b. Maintains the song’s tempo or speed

c. Provides a foundation for the rest of the instruments and voices

d. All of the above

_______________________________

a. Refrain or chorus

b. Verse

c. Melody

d. Harmony

_______________________________

a. National song

b. Religious or sacred song

c. Children’s song

d. Classical song

_______________________________

a. Rock music

b. The blues

c. Classical music

d. Techno

_______________________________

a. A classical symphony

b. Rock ‘n’ roll or pop music

c. Folk songs

d. None of the above

|

Activity 1E THINK ABOUT IT How would you describe your relationship with music? Do you typically spend more time listening to music or making it? How much time do you spend listening to music through headphones? Listening to music with other people? Keep track of how much music you encounter in one day. How much of it is pre-recorded? How much of it is live? |

If human beings are innately musical, and if in some societies these innate capacities are nurtured in early childhood, it has always seemed to me that we must do more in modern industrial society to place artistic experience and musical practice at the center of education. (Blacking, 1991, p. 55)

What if you heard of a new product that could help children focus, increase their learning potential, re-boot their cognitive functioning, and make them feel relaxed and refreshed all in a few minutes? And best of all, it’s free! Would you use it?

Music is powerful, and music has the power to change people emotionally or alter the mood of room with just a few simple notes or beats. Music, as energy, has the ability to transform all those within its reach. We turn to music to feel better, relieve anxiety, overcome a difficult situation, find calm and peace, or feel empowered and fearless. Although we don’t take much time in our busy day to think about it, one of the most significant uses for music is to create an aesthetic experience. An aesthetic response or experience concerns the nature of beauty, art, and taste. Children are capable of appreciating beauty in art, music, language, and movement. Exposure to these artistic forms develops the inner core of a child, introduces new dimensions of possibilities, and shows the brain a new way of functioning and understanding. The other good news is that it only takes a couple of minutes and a little thought to achieve this, and put some of the basic elements of music to work. Timbre, tempo, and dynamics are so powerful that a few adjustments here and there can change the entire learning atmosphere of a classroom.

For example:

|

Activity 1F THINK ABOUT IT How might you go about creating an aesthetic experience (in or out of a classroom)? What if you had only a few instruments? No instruments at all? How could you accomplish an aesthetic transformation using sound? |

Before we discuss our cultural ideas of what music is, we first need to understand that music is only part of the larger category of sound. The sounds all around us play a significant role in our development. We spend our lives surrounded by all kinds of sounds that are unique to our environment, yet we rarely pay attention to them. As a child grows, he or she becomes acculturated to all of the sounds in their environment. These include not only all of the genres of music, the verbal languages, and accents, but also the mechanical, digital, human, and animal noises, and all of the ambient sounds around us. All of these combine to create our acoustic environment. This soundscape, as acoustic environmentalist R. Murray Schafer conceived it, concerns what those sounds tell us about who we are and the time in which we live.

Our soundscapes have tremendous physical and cognitive impacts on us. The soundscape affects our health, body, and learning. For example, a child’s environment in a city will be vastly different than one in the country, or the soundscape of 1,000 years ago differs dramatically from a soundscape today.

As Schafer began his work on understanding the sonic environment, he realized that we don’t have a very specific vocabulary to describe sounds—what we’re hearing and how we’re hearing it. Whereas visual vocabulary tends to be more detailed, we lack nuanced conceptual words to describe sound and our relationship to it. Schafer coined the terms keynote, soundmark, and sound signal to distinguish between different types of sounds, their connections to the environment, and our perception of them.

Keynote: As a musical term, keynote identifies the “key” of a piece. Although you may not always hear the key, and the melody may stray from the key, it always returns back to the key. A keynote “outlines the character of the people living there.” Keynotes are often nature sounds (wind, birds, animals, water) but in urban areas can be traffic. The keynote sound for New York City might be horns of Yellow cabs and cars, for example.

Soundmark: This term is inspired by the word “landmark” and refers to the sound unique to an area. A landmark is something that is easily recognizable (e.g., the Eiffel Tower, Monument Valley, Grand Canyon, Empire State Building). Now think of a location and its sound, and imagine a recognizable sound associated for that place.

Sound signal: A foregrounded sound that we consciously hear. Sound signals compel us to pay attention to something. Some examples are warning devices, bells, whistles, horns, sirens, etc.

Shafer also makes interesting distinctions between the sources of sound. Some sources are made by nature, such as wind, water, and waves; some are human-made such as singing, speech, and stomping; some are made by animals, such as calls, cries, and growls; some are machine-made clanks, whistles, whirrs, and beeps. Schafer coined the term schizophonia to describe sound that is separated from its source, such as recorded music. Because most of the music we listen to is not live but recorded, schizophonia is a concept crucial to describe and understand a child’s (and our own) relationship to sound and our environment.

|

Activity 1G Think About It What would it sound like if you lived 100 years ago? 200? 500? 1,000? How did people hear music back then? Where did they have to go to hear music? How was music made? What sounds would be keynote sounds or soundmarks? Human-made vs. machine- or animal-made? What sounds would dominate in each of those times? Children’s Soundscape I. Sit quietly for five minutes and listen to the sounds around you. Now write down the sounds and describe them. Describe the quality or tone color of each sound (timbre) of each sound. How might you draw or visually represent these sounds and their timbres? What is the sound’s source? How might you categorize these sounds (i.e., human, electronic, animal, machine-made)? II. Describe any revelations or thoughts that you’ve had during this experience. Now, explain a creative way to adapt this project for children. How could children benefit from hearing sounds in a new way? What activities could you do with them to underscore the idea of the soundscape? Develop three activities along the lines of Schafer’s ideas. |

Important Children’s Music Collections

Appel, M. P. (2006). Arts integration across the curriculum. Leadership, Nov./Dec., 14–17.

Birth.com.au. (2013). Feeling your baby move. From Bellies to Babies & Beyond.

Blacking, John. (1985) “Versus Gradus novos ad Parnassum Musicum: Exemplum Africanum “ Becoming Human through Music: The Wesleyan Symposium on the Perspectives of Social Anthropology in the Teaching and Learning. Middletown: Wesleyan University. Music Educators National Conference, 43-52.

Campbell, P. (1998). Songs in their heads: Music and its meaning in children’s lives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Flake, C. L. E. (1993). Holistic Education: Principles, Perspectives and Practices. A Book of Readings Based on “Education 2000: A Holistic Perspective.” Brandon, VT: Holistic Education Press.

Goldberg, M., and Bossenmeyer, M. (1998). Shifting the role of arts in education. Principal, 77, 56–58.

Gordon, E. (2012). Newborn, preschool children, and music: Undesirable consequences of thoughtless neglect. Perspectives: Journal of the Early Childhood Music and Movement Association, 7(3-4), 6-10.

Gullatt, D. E. (2008). Enhancing student learning through arts integration: Implications for the profession. The High School Journal, 85, 12–24.

Hallam, S. (2010). The power of music: Its impact on the intellectual, personal and social development of children and young people. In S. Hallam, Creech, A. (Eds.), Music education in the 21st century in the United Kingdom: Achievements, analysis and aspirations (pp. 2-17). London: Institute of Education.

Howard, K. (1991). John Blacking: An interview conducted and edited by Keith Howard. Ethnomusicology 35(1), 55–76.

Jensen, E. (2002). Teach the arts for reasons beyond the research. The Education Digest 67(6), 47–53.

Kim, H. K. (2007). Early childhood preservice teachers’ beliefs about music, developmentally appropriate practice, and the relationship between music and developmentally appropriate practice. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL.

Mayes, C. (2007). Understanding the whole student: Holistic multicultural education. Washington, DC: Rowman and Littlefield.

Miller, J. (2007). The holistic curriculum. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

Rabkin, N., & Redmond, R. (2006). The arts make a difference. Educational Leadership, 63(5): 60–64.

Ruppert, S. S. (2006). Critical evidence: How the arts benefit student achievement. Washington, DC: National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. Retrieved from http://www.nasaa-arts.org/Publications/critical-evidence.pdf

Schafer, R. M. (1993). Our sonic environment and the soundscape: The tuning of the world. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books.

Weinberger, N. (1998). The music in our minds. Educational Leadership, 56(3), 36–40.

Wagner, T. (2010). The global achievement gap: Why even our best schools don’t teach the new survival skills our children need—and what we can do about it. Philadelphia, PA: Basic Books.

acculturated: accustomed to; to assimilate the cultural traits of another group

aesthetic: how one experiences music; one’s personal musical experience

ambient: of the surrounding area or environment

enculturation: learning through experiencing one’s culture; the process whereby individuals learn their group’s culture, through experience, observation, and instruction

genres: the different styles of music found in any given culture; a class or category of artistic endeavor having a particular form, content, or technique

idioms: musical styles, genres, and characteristics

schizophonia: R. Murray Schafer’s coined term to describe sound that is separated from its source; recorded music is an example of schizophonic sound because the musicians are not performing the music live in front of you

sound: what we hear; the particular auditory effect produced by a given cause

soundscape: all the ambient sounds around us; the sounds that are part of a given environment

sound waves: the vibrations felt by people that come from musical instruments or voices; a longitudinal wave in an elastic medium, especially a wave producing an audible sensation

timbre: the tone color of each sound; each voice has a unique tone color (vibrato, nasal, resonance, vibrant, ringing, strident, high, low, breathy, piercing, rounded warm, mellow, dark, bright, heavy, or light)

Western culture: culture influenced by Europe, the Americas, and Australia; the modern culture of Western Europe and North America

Library Info and Research Help | reflibrarian@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4215

Loans or Fines | circ@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4222

475 Grand Concourse (A Building), Room 308, Bronx, NY 10451