Adapted by Denise Cummings-Clay

Conditions of Use:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Chapters derived from:

https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/music-and-the-child

by Natalie Sarrazin

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License.

Click on the printer icon at the bottom of the screen

![]()

Make sure that your printout includes all content from the page. If it doesn't, try opening this guide in a different browser and printing from there (sometimes Internet Explorer works better, sometimes Chrome, sometimes Firefox, etc.).

If the above process produces printouts with errors or overlapping text or images, try this method:

Chapter Summary. Allowing all children equal access to an art form is more difficult than it sounds. Social pressures, stereotypes, and changing attitudes and perspectives can inhibit inclusion and lead to exclusionary practice. This chapter addresses the issue of several types of musical inclusion, including music and gender, and music for children with autism, ADD/ADHD, learning and physical disabilities.

Most of us never consider whether music is gendered, but any system that is part of a culture, even a musical one, is bound to include any general perceptions and values of the society as a whole.

What is gender? The term sex refers to the biological and physiological characteristics that define men and women, while gender refers to society’s constructed roles, expectations, behaviors, attitudes, and activities that it deems appropriate for men and women. Many of us can remember the first time we became aware of our gender. For some, it was an article of clothing that was too “boyish” or “girlish” to wear, while for others it was noticing certain behaviors such as preferring to play with trucks and cars rather than dolls, and realizing the societal expectations that encourage boys to play with trucks and cars. We incorporate gender into all aspects of our daily lives from a very early age onward, and can be socially uncomfortable if we are unsure of someone’s gender or have issues coming to understand our own.

Perceptions of the individual based on their gender and race influence all of us in all areas. We contextualize, filter, draw conclusions, and make inferences, in part, based on someone’s physical attributes. Many educators have studied the role of gender and how it affects teachers and teaching. For example, individual teachers may prefer one gender to another, but the entire educational system in general, favors girls’ learning styles and behaviors over that of boys. Grades are affected in addition to access to certain opportunities and promotion to leader- ship roles. Boys and girls may express different musical interests and abilities with girls showing self-confidence in literacy and music and boys showing confidence in sports and math, but teachers also discuss boys and girls musicality differently (Green, 1993).

Is music gendered? Music is highly gendered in ways that we might not even think about. Societies attribute masculinity to different genres of music, instruments, and what musicians should look like when performing. For example, genres like heavy metal and rock are gendered not only in the fact that male musicians dominate them, but also in that they are perceived as male-oriented in subject matter, with appeal to a male audience. Gender lines are not as straightforward as one might believe, however. In performance, there is a great deal of gender bending or borrowing that can occur. On stage, male musicians may co-opt female gendered attributes as part of a performance, such as Heavy or Hair Metal band members wearing long hair and make-up.

Musical instruments are also “gendered.” Our choices as to which instrument to play, in other words, are not entirely our own. Society, friends, and teachers, play a significant role in our music selection process. As a culture, and even as children, we have very particular notions of who should play what instruments, with children as young as three associating certain instruments with gender (Marshall and Shibazaki, 2012). In a 1981 study, Griswold & Chroback found that the harp, flute, and piccolo had high feminine ratings; the trumpet, string bass, and tuba had high masculine ratings.

As Lucy Green mentions above (1993), boys and girls have different musical interests, and teachers discuss musicality differently regarding boys and girls, and are likely to offer differences in opportunity, instrument selection, etc. For example, according to a 2008 study, girls are more likely to sing, while boys are more likely to play instruments such as bass guitar, trombone, and percussion. One interesting exception to boy’s dominance of percussion is that, participation in African drumming was far more egalitarian, with an equal number of boys and girls playing (Hallam, 2008, p. 11-13).

|

Activity 11A Think about it You might have an early memory when deciding what instrument to play in the school band or for lessons at home. Why did you decide on which instrument to play? Were you influenced by what instrument other girls or boys or professional musicians were playing? Did your parents or teachers encourage you in one direction or another? |

Throughout this book, we’ve learned about the many connections that music has on mental and emotional development. Music, is of course, more than entertainment, and affects the body directly through its sound vibrations. Our bodies are made up of many rhythms—the heart, respiratory system, our body’s energy, digestive systems etc. These vibrations result in something called entrainment, where our bodies try to sync up with the tempo of the music. Music can affect our heartbeat, blood pressure, and pulse rate, and reduce stress, anxiety and even depression.

The fact that the body and mind are so affected by music forms the basis for most music therapy. Music Therapy is defined as “A systematic process of intervention wherein the therapist helps the client to achieve health, using musical experiences and the relationships that develop through them as dynamic forces of change” (Bruscia, 1989, p. 47). “Musical experiences can include singing or vocalizing, playing various percussion and melodic instruments, and listening to music…Music therapists tap into the power of music to arouse emotions that can be used to motivate clients” (Pelliteri, 2000).

Music can be used to create any number of environments for children to flourish cognitively and developmentally. Music creates a general sense of well being, while creating a positive environment in which to learn, create, and function. For example, playing soft classical music, particularly Baroque music (Bach, Vivaldi, etc.) increases attention and the ability to concentrate, allowing the listener to work more productively.

Music also has a direct impact on the heart rate. The heart responds by beating more quickly when listening to faster tempos, and slower when listening to slower tempos. It also responds to dynamics (loud and soft) and to certain pitch frequencies.

Activity |

Music |

|

High energy activities

|

130 beats per minute

|

|

Medium energy activities

|

80–100 beats per minute

|

|

Lower energy activities

|

60–80 beats per minute

|

In addition to the beats per minute (tempo), the timbre, expression, and volume (dynamics) of a song also have an impact. For example, a loud orchestral piece, even if it has 60 beats per minute, will not aid the body into a calm state as well as a softer, more soothing piece with a few instruments. Low-pitched instruments such as drums impact the body with vibration and rhythm that influence body rhythms and movement, whereas higher-pitched frequencies such as flute and voice demand more attention and focus. Pieces such as Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or Orff’s Carmina Burana, for example, would not be good choices as they are likely to promote agitation and frenetic activity rather than concentration and productivity.

|

Activity 11B Try This Go to a website such as Pandora (www.pandora.com), Stereomood (www.stereomood.com) or Spotify (www.spotify.com). Select different types of music and note down the general beats per minute using a watch or clock. Then take stock of your physical reactions. For example, how do you respond to the workout genre on Pandora? Does your heart rate increase? Are you able to concentrate with this type of music in the background? What about the easy listening genre? Compare: Does the Music Therapy selection on the Mood/Relaxed channel on Spotify create the same physical reaction as any of the classical adagio selections suggested above? How about the Mood Booster channel? How does Stereomood compare in terms of changing your mood? Document any physical reactions you might have had. |

Any group of students has a wide range of abilities, and each child presents a unique challenge in terms of the best way to reach their maximum learning potential. Some students may be gifted or already familiar with the material, while others are challenged simply by the arrangement of the room. Some children, however, require more extensive modifications to the curriculum in order to succeed. Regardless of where you work, you are likely to be in a position where you will encounter students that require additional help.Music can greatly assist these children in a variety of ways, helping and nurturing them in learning and development.

The strategies outlined below can be used in any general music work with children, but are particularly helpful techniques aimed at aiding individuals with specific needs. Many of the techniques introduced in this textbook are used in music therapy and to treat Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD). Musical activities such as singing, singing/vocalization, instrument play, movement/dance, musical improvisation, songwriting/composition, and listening to music, are types of musical therapy interventions to assess and help individuals practice identified skills.

As with selecting any material for any child, you will need to assess the particular needs of the student, including speech and developmental levels. If the child is pre-verbal or verbally limited, a simple song (limited lyrics, simple phrases) would be more appropriate than something complex.

Musical activities, including singing or playing instruments, can increase the self-esteem level of the child. Pamela Ott suggests asking the following questions when selecting material, keeping in mind that simply doing the activity successfully is one of the most important goals (Ott, 2011):

Often children require a well-structured day in which to work successfully. In addition to integrating music in the day, as discussed in the next chapter as well, music can also help to organize and structure the day for children who have trouble transitioning from activity to activity.

Possible uses for music throughout the day include:

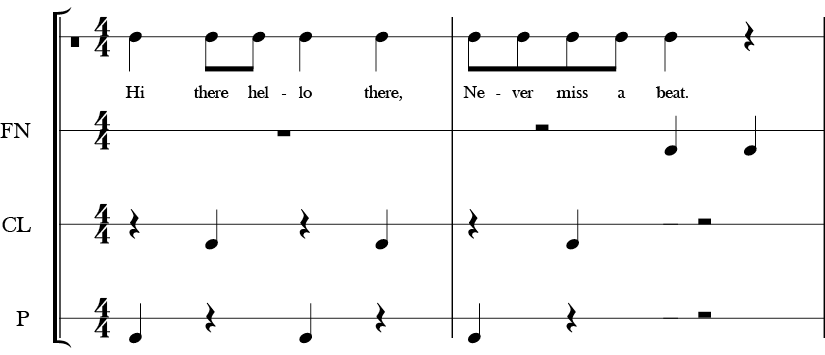

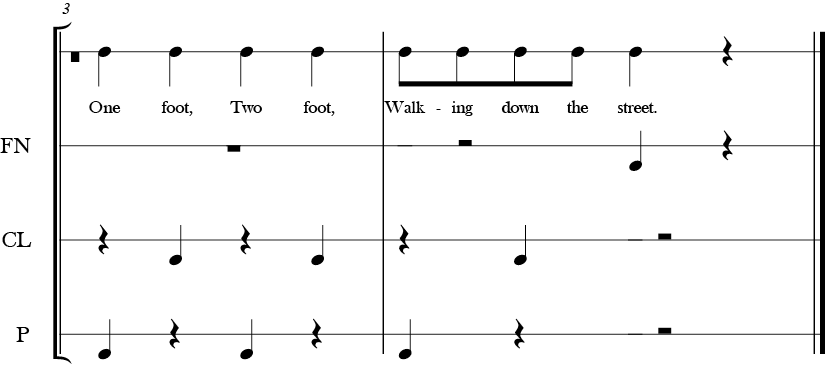

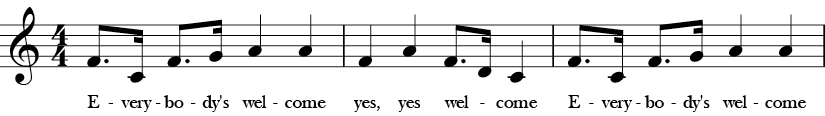

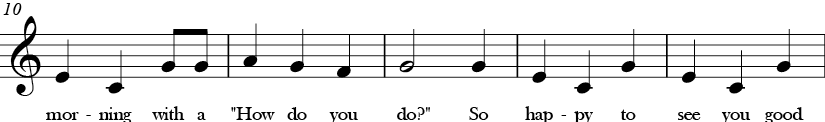

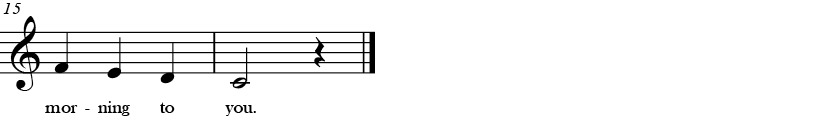

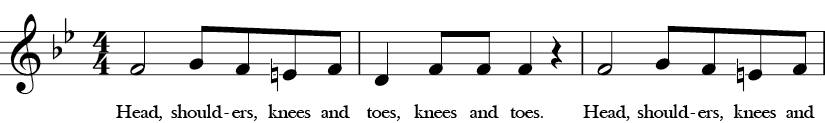

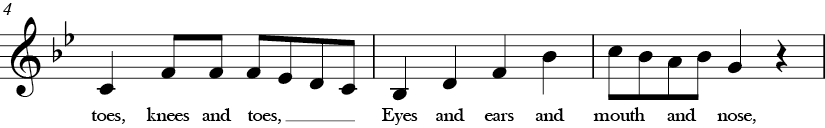

Examples of Hello rhymes and songs might include “Hi There, Hello There.” If the body percussion is too complex, simply say the rhyme or clap to the rhyme.

For children who are pre-verbal or speech-delayed, substituting nonsense syllables helps them successfully sing a favorite tune. “Doo,” “boo,” “la,” etc., are easily pronounceable and fun for children to articulate.

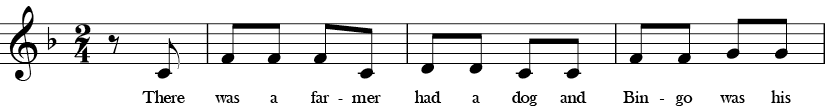

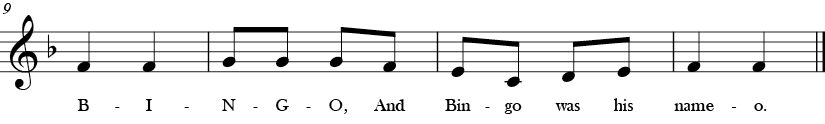

Other familiar songs to help increase verbal awareness include songs with word sub- stitutions or nonsense syllables such as Sarasponda or Supercalifragilisticexpialidocous. The song B-I-N-G-O is an excellent example in which to practice internalizing the pitch since the singer has to clap the rhythm and silently think the pitch in their head.

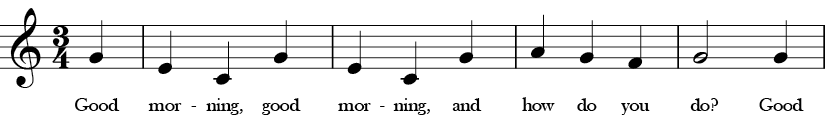

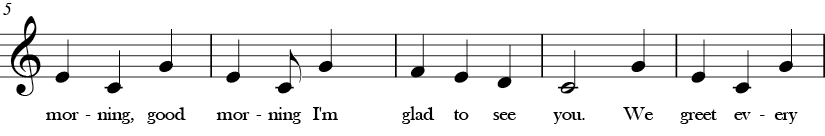

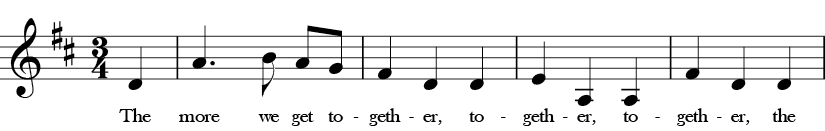

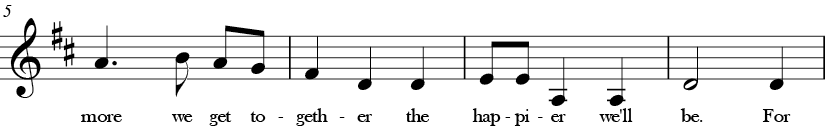

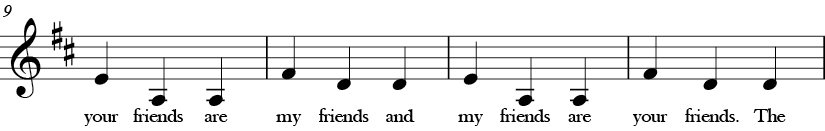

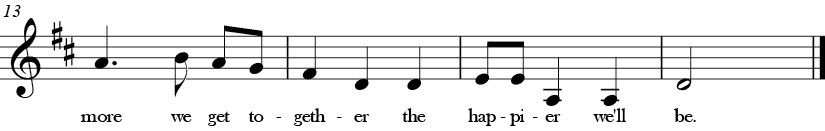

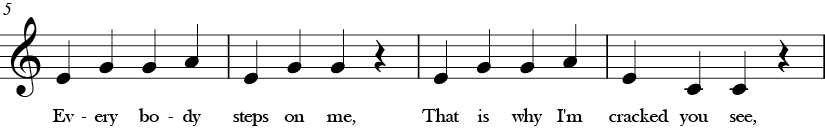

American play party song

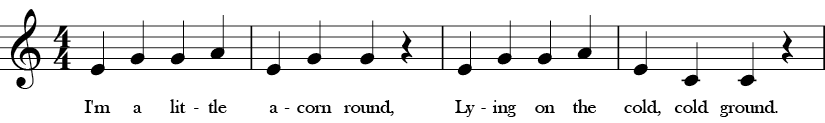

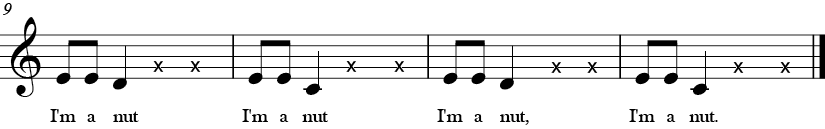

Another song with an opportunity for children to insert a rhythm is “I’m a Nut.” Although the song does have quite a few words, the refrain is repetitive with only three words, and provides two empty beats for clapping or playing an instrument.

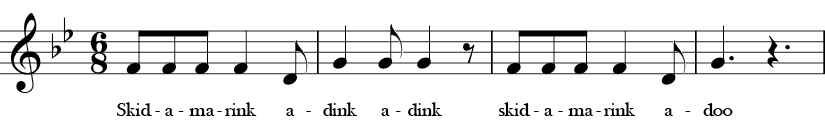

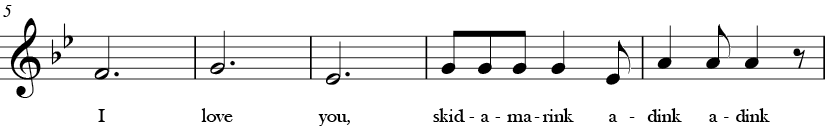

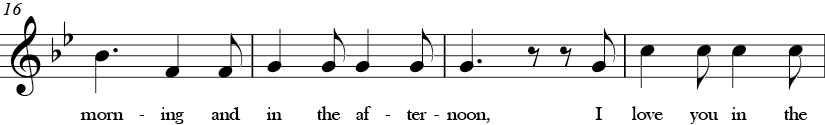

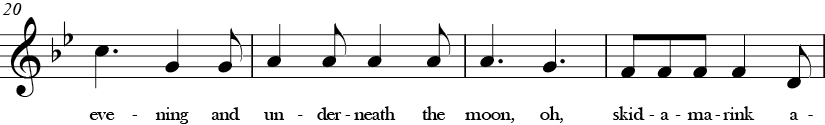

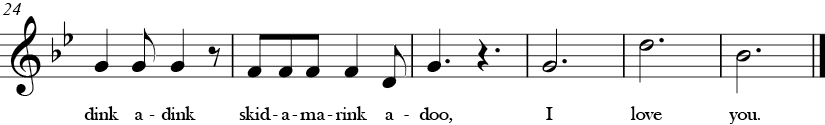

Any song can be adapted to allow the insertion of rhythm simply by substituting a word or phrase with a clap (or instrument). The substituted word or phrase can be part of the rhyme or not. For example, in the silly song “Skidamarink,” the phrase “I love you” can be clapped, or even just the “you.” Words such as “morning” “afternoon” “moon,” etc. are also good candidates for substitution.

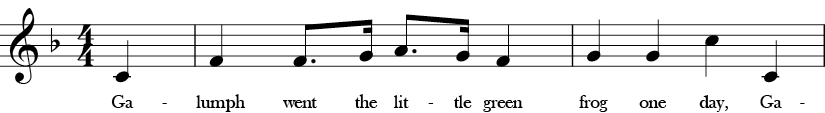

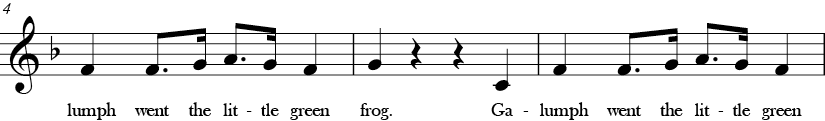

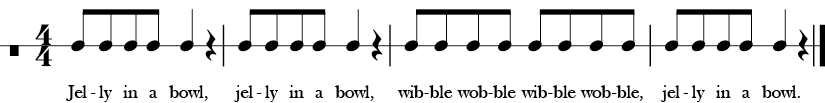

Silly songs and rhymes with interesting onomatopoeic sounds and simple, repetitive words are also highly useful, such as “Galumph Went the Little Green Frog” and “Jelly in a Bowl.”

The remainder of the chapter contains material from the National Association for Music Educators regarding some tips and general strategies for working with children who have special needs.1

Many classrooms today are inclusive, meaning that they will include children who have special needs. Preparing to help these children requires additional thought and strategies.

Debrot (2002) says you can address a variety of skill levels in one piece of music: While some children play complex patterns, others can sing or play a simple steady beat. “Every student has a learning style that is unique,” says Debrot. “Presenting material aurally, visually, tactilely, and orally will insure that you connect with the varied learning styles for all students. The use of speech, movement, instruments, and singing in each lesson will insure that each child feels some degree of success.”

Music has been found to be successful in working with children who have Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Using music activities and songs helps to greatly increase independent performance and reduce anxiety. Music was found to help reduce the stress of transitions such as the shift from home to school, help children remember step-by-step routines like clean up time, and also increase the community and group inclusion of children with and without disabilities (Kern, 2004).

Iseminger (2009) refers to employing an “Intentional Approach” when dealing with students on the autism spectrum, particularly those with difficulty with transitions. The following examples are helpful in preparing autistic students in advance for transitions.

Shore’s work (2002) explains the musical benefits for those on the autism spectrum. Music provides an alternative means of communication for nonverbal students, and can also help other verbal students organize their communication. Music can help to improve children’s self-esteem in that they can participate and possibly excel in the musical endeavor. Music is also a social and communal activity, and a child with autism can enter into the communal and social interaction of music making.

Iseminger (2009) notes that two main areas where teachers can help students with autism are in creating appropriate visual aids and achieving predictability. “Children with special needs are concrete learners, and visual information makes words more concrete. Pictures of a student sitting in a chair or playing the recorder give clear directions. Those on the autism spectrum are often stronger visual than auditory learners and have a tremendous need for visual information.” Also, autistic children act out due to increased anxiety and fear, not from autism itself. As a classroom teacher, taking steps to minimize anxiety will help with managing classroom behavior.

Most teachers use some type of visual cues and supports such as charts, books, musical instruments, and music notation. Making these visuals simple and accessible will greatly help autistic children in the class.

“Sometimes you just have to plow through the struggle or upset to establish the routine,” says Iseminger. “They are taking it in, despite what it looks like, calming down after one or two class sessions.”

Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) are two of the most common factors for special needs in today’s classrooms. ADD and ADHD are disabilities and fall under the designating category of “Other Health Impairment.” This NAfME post addresses both issues and gives guidance to mediate its effects in the classroom.

Many teachers recognize the signs of attention deficit disorder (ADD) and attention deficit hyperactive disorder (ADHD): an inability to maintain attention, impulsive behaviors, and/or motor restlessness. Students can have mild, moderate, or severe symptoms and can be found in both general education and special education classes.

Elise S. Sobol teaches at Rosemary Kennedy School, Wantagh, New York (for students with multiple learning disabilities, including those with autism and developmental difficulties) and is the chairperson of Music for Special Learners of the New York State School Music Association.

Sobol (2008) suggests the following strategies for students with ADD with or without hyperactivity:

Sobol subscribes to William Glasser’s Choice Theory: Students will do well if four basic needs are addressed in the educational classroom or performance setting. All students need to feel a sense of:

“Students with behavior disorders are generally unhappy individuals, and they often make everyone around them unhappy as well,” says NAfME member Alice-Ann Darrow (2006) “They’re generally disliked by their peers, their teachers, their siblings, and often even their parents.” They may also be diagnosed with learning disabilities, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorders, depression, and suicidal tendencies.

Darrow recommends some instruction accommodations:

Darrow also uses strategies from Teaching Discipline by Madsen and Madsen (1998):

Adapt your expectations of students and your instruction. “Appropriate behaviors have to be shaped—shaped through successive approximations to the desired behavior,” says Darrow. “Shaping desired behaviors takes time.” When starting, she recommends accepting and reinforcing behaviors that come close to the desired behavior.

Developing more positive attitudes about teaching students with behavior disorders goes a long way to reduce the stress of teaching them.

More students with physical disabilities, orthopedic conditions, and fragile health are participating in school music programs. Elise Sobol, chairperson of Music for Special Learners of the New York State School Music Association, offers some advice:

“Technological advances such as the innovative SoundBeam,” says Sobol, “allow 100% accessibility to students with even the most severe limitations to experience the joy of making music, exploring sound, creating compositions, and performing expressively.”

The British SoundBeam system translates body movement into digitally generated sound and image. This technology is available in the U.S. through SoundTree. Click on “Music Education,” then on “Music Therapy.”

“Although it may be challenging for teachers to find adaptive instruments to suit the individual needs of their students,” Sobol says, “the music market catalog offerings are expanding.” See distributors such as West Music, Music Is Elementary, Musician’s Friend, among others.

Sobol finds the following helpful:

Sobol has found success with the following:

Students who are deaf or hard of hearing can succeed in music class. MENC member Elise Sobol shares some of her instructional strategies.

The following suggestions may also be helpful:

Visual impairments range from low vision to blindness and can demand a variety of strategies. MENC member Elise Sobol urges educators to work closely with the special education team in their school district including the assigned vision teacher where applicable, and consult the student’s Individual Educational Program (IEP) to match any and all accommodations and learning supports.

These supports may include an assistive device such as a cane, technology and transcription software such as a Braille printer to translate text and music, a therapy animal such as a seeing-eye dog, or a teacher aide, depending on the student’s educational needs.

Sobol has had success with the following:

Sobol recommends reading the following in the classroom:

Alden, A. (1998). What does it all mean? The National Curriculum for Music in a multi-cultural society. (Unpublished MA dissertation). London University Institute of Education, London.

Armstrong, V. (2011). Technology and the gendering of music education. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate.

Davidson, J. and Edgar, R. (2003). Gender and race bias in the judgment of Western art music performance. Music Education Research, 5(2), 169-181.

Eccles, J., Wigfield, A., Harold, R., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and ender differences in children’s self- and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64(3), 830-847.

Green, L. (1993). Music, gender and education: A report on some exploratory research. British Journal of Music Education, 10(3), 219-253.

Green, L. (1997). Music Education and Gender. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Green, L. (1999). Research in the sociology of music education: Some introductory concepts. Music Education Research, 1(1), 159-70.

Griswold, P., & Chroback, D. (1981). Sex-role associations of music instruments and occupations by gender and major. Journal of Research in Music Education, 29(1), 57-62.

Hallam, S. (2004). Sex differences in the factors which predict musical attainment in school aged students. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education,

161/162, 107-115.

Hallam, S., Rogers, L. Creech, A. (2008). Gender differences in musical instrument choice. International Journal of Music Education. 26 (1), 7-19.

Marshall, N., & Shibazaki, K. (2012). Instrument, gender and musical style associations in young children. Psychology of Music, 40(4), 494-507.

O’Neill, S. A.,Hargreaves, D. J., & North, A. C. (Eds.) (1997). The social psychology of music. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Iseminger, S. (2009). Keys to success with autistic children: Structure, predictability, and consistency are essential for students on the autism spectrum. Teaching Music, 16(6), 28.

Kern, P. (2004). “Making friends in music: Including children with autism in an interactive play setting. Music Therapy Today, 6(4), 563-595.

Shore, S. M. (2002). The language of music: Working with children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Education, 183(2), 97-108.

Hourigan, R. (2009). Teaching music to children with autism: Understandings and perspectives. Music Educators Journal, 96, 40-45.

Bruscia, K. (1989). Defining music therapy. Spring Lake, PA: Spring House Books.

Eagle, C. (1978). Music psychology index. Denton, TX: Institute for Therapeutic Research.

Campbell, D., & Doman, A. (2012). Healing at the speed of sound: How what we hear transforms our brains and our lives. New York, NY:Plume Reprints.

Campbell, D. (2001). The Mozart effect: Tapping the power of music to heal the body, strengthen the mind, and unlock the creative spirit. New York: Quill.

Debrot, R. A. (2002). Spotlight on making music with special learners: Differentiating Instruction in the Music Classroom. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Hodges, D. A. (Ed.). (1980). Handbook of music psychology. Dubuque, IA: National Association for Music Therapy.

Ott, P. (2011). Music for special kids. Philadelphia, PA: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Pelliteri, J. (2000). Music therapy in the special education setting. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 11(3/4), 379-91. Retrieved from http://www.soundconnectionsmt.com/docs/Music%20Therapy%20in%20Special%20Education.pdf

Sobol, E. (2008). An attitude and approach for teaching music to special learners. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hourigan, R. (2008). Teaching strategies for performers with special needs. Teaching Music 15(6), 26.

Hourigan, R, and Hourigan, A. (2009). Teaching Music to Children with Autism: Understandings and Perspectives. Music Educators Journal 96(1), 40-45.

Adamek, M., & Darrow, A. (2005). Music in Special Education. Silver Spring, MD: The American Music Therapy Association, Inc.

Darrow, A. (2006).Teaching students with behavior problems. General Music Today, Fall 20 (1) 35-37

Madson, C., & Madsen, C. (1998). Teaching discipline: A positive approach for educational development (4th ed.). Raleigh, NC: Contemporary Publication Company of Raleigh.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)/Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD): a psychiatric disorder characterized by significant problems of attention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity not appropriate for a person’s age

Autism: a neural development disorder characterized by impaired social interaction and verbal and non-verbal communication. One of three recognized disorders on the Autism Spectrum, which includes Asperger Syndrome and Pervasive Developmental Disorder

disability: a disability, resulting from an impairment, is a restriction or lack of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being (World Health Organization)

entrainment: the patterning of body processes and movements to the rhythm of music

gender: the constructed roles, expectations, behaviors, attitudes, and activities deemed appropriate for men and women

music therapy: a health profession in which music is used within a therapeutic relationship to address physical, emotional, cognitive, and social needs of individuals

sex: biological and physiological characteristics that define men and women

1 Reprinted with permission. Copyright NAfME, 2012, http://www.nafme.org/strategies-for-students-with-special-needs/

2 Reprinted with Permission from NAfME http://www.nafme.org/success-with-autism-predictability © National Association for Music Education

3 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://nafme.org/tips-for-teaching-students-with-add-or-adhd/ © MENC: The National Association for Music Education (menc.org)

4 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://www.nafme.org/teaching-students-with-behavior-problems/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)

5 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://www.nafme.org/dont-let-physical-disabilities-stop-students/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)

6 Reprinted with permission from NAfME http://nafme.org/interest-areas/guitar-education/music-and-students-with-hearing-loss/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)

7 Reprinted with permission for NAfME http://www.nafme.org/strategize-for-students-with-vision-loss/ © National Association for Music Education (nafme.org)

Library Info and Research Help | reflibrarian@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4215

Loans or Fines | circ@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4222

475 Grand Concourse (A Building), Room 308, Bronx, NY 10451