Architecture is an art form that reflects how we present ourselves across the earth’s landscape, and, like other expressive mediums, it changes with styles, technologies and cultural adaptations. Architecture not only provides worldly needs of shelter, workspace and storage but also represents human ideals in buildings like courthouses and government buildings and manifestations of the spirit in churches and cathedrals. Traditional architecture has survived over thousands of years in one form or another, while contemporary design offers new approaches in how we use materials and technology to shape the look of our environment.

Early Developments in Building Design and Techniques Methods

The basic methods of building design and construction have been used for thousands of years. Stacking stones, laying brick, or lashing wood together in one form or another are still used today in all parts of the world. But over the centuries, innovations in methods and materials have given new expression to architecture and the human footprint on the landscape. We can look to historical examples for clues that give context to different style periods.

In western culture, one of the earliest settlements with permanent structures was discovered at Catalhoyuk in Turkey (pictured below). The rich soil that surrounds the settlement indicates the inhabitants relied in part on farming. Dated to about 7500 BCE, the dwellings are constructed from dried mud and brick and show wooden support beams spanning the ceilings. The design of the settlement incorporates a cell-like structure of small buildings either sharing common walls or separated by a few feet. The roofs are flat and were used as pathways between buildings.

Restoration of interior, Catalhoyuk, Turkey. Image licensed under Creative Commons.

A significant advance came with the development of the post and lintel system. With this, a system of posts –either stone or wood – are placed at intervals and spanned by beams at the tops. The load is distributed down the posts to allow for areas of open space between them. Its earliest use is seen at Stonehenge (below), a prehistoric monument in southern England dating to about 3000 BCE.

Stonehenge, Wiltshire County, England. Image: David Ball. Image licensed under Creative Commons.

Post and Lintel support in contemporary use. Image by Christopher Gildow. Used with permission.

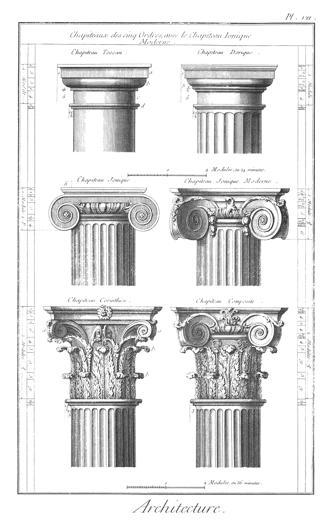

A colonnade continues the post and lintel method as a series of columns and beams enveloping larger areas of space. Colonnades can be free standing or part of a larger structure. Common in Egyptian, Greek and Roman architectural design, their use creates visual rhythm and implies a sense of grandeur. Over time columns became categorized by the capital style at their tops. The smooth and unadorned Tuscan and fluted Doric columns give way to more elaborate styles: the scrolled Ionian and the high relief Corinthian.

Greek and Roman capitals: Top row: Tuscan, Doric. Middle Row: Ionic. Bottom Row: Corinthian and a composite Ionic Corinthian. Classical Orders, engraving from the Encyclopédie vol. 18. Public domain.

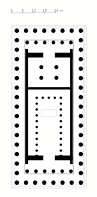

The Parthenon, a Greek temple to the mythic goddess Athena, was built in the fifth century BCE in Athens and is part of a larger community of structures in the Acropolis. All are considered pinnacles of classic Greek architecture. Ionic colonnades march across all sides of the Parthenon, the outer boundary of a very ordered interior floor plan.

The Parthenon, Athens, Greece. 447 BCE. Digital image by Kallistos and licensed under Creative Commons

Floor plan of the Parthenon. Licensed through Creative Commons.

Another example is the colonnade surrounding St. Peter’s Square in the Vatican, Rome.

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Colonnade at St. Peter’s Square, the Vatican. 1656–67. Photo by D.F. Malan. Licensed through Creative Commons.

The colonnade is part of our contemporary surroundings too. Parks and other public spaces use them to the same effect: providing visual and material stability in spanning areas of open space.

Contemporary colonnade. Image: Christopher Gildow. Used with permission.

The development of the arch gave architecture new alternatives to post and lintel construction. Arches appeared as early as the 2nd millennium BC in Mesopotamian brick architecture. They supply strength and stability to walls without massive posts and beams because their construction minimizes the shear load imposed on them. This meant walls could go higher without compromising their stability and at the same time create larger areas of open space between arches. In addition, the arch gave buildings a more organic, expressive visual element. The Colosseum in Rome (below), built in the first century CE, uses repeated arches to define an imposing but decidedly airy structure. The fact that it’s still standing today is testament to the inherent strength of the arch.

The Colosseum, Rome, Italy. First century CE. Photo by David Iliff. Image licensed through Creative Commons.

Roman aqueducts are another example of how effectively the arch was used. Tall and graceful, the arches support themselves in a colonnade and were used to transport a network of water channels throughout ancient Rome.

Roman aqueduct, c. First century CE. Image in the public domain.

From the arch came two more important developments: extending an arch in a linear direction formed a vault, encapsulating tall, narrow spaces with inverted “U” shaped ceilings. The compressive force of the vault required thick walls on each side to keep it from collapsing. Because of this many vaults were situated underground – essentially tunnels – connecting areas of a larger building or providing covered transport of people, goods and materials throughout the city.

An arch rotated on its vertical axis creates a dome, with its curving organic scoop of space reserved for the tops of the most important buildings. The Pantheon in Rome sports a dome with an oculus – a round or elliptical opening at the top, that is the massive building’s only light source.

Dome of the Pantheon with oculus, Rome. 126 CE. Image in the public domain.

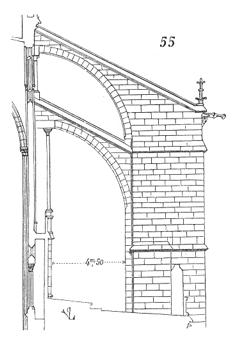

These elements combined to revolutionize architectural design throughout Europe and the Middle East in the form of bigger and stronger churches, mosques and even sectarian government buildings. Styles changed with technology. Romanesque architecture was popular for nearly three hundred years (800 – 1100 CE). The style is characterized by barrel or groin vault ceilings, thick walls with low exterior buttresses and squared off towers. Buildings reached a point where they struggled to support their own weight. The architectural solution to the problem was a flying buttress, an exterior load-bearing column connected to the main structure by a segmented arch or “flyer.”

Diagram of a flying buttress from St. Denis basilica, Paris. From the Dictionary of French Architecture from 11th to 16th Century (1856), licensed through Creative Commons.

Flying buttresses became a kind of exoskeleton that transferred the heavy weight of Romanesque stone roofs through their arches and into the ground, away from the building. They became catalysts for the Gothic style based on higher, thinner walls, pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and spired towers. Also, the thinner walls of the Gothic style allowed for more stained glass windows and interior illumination.

Church of St. Denis, France. Seventh–twelfth centuries CE. Image in the public domain

St. Denis basilica in France (above) is one of the first Gothic-style churches, known for its high vaulted ceilings and extensive use of stained glass windows. The architecture of the church became a symbol of spirituality itself: soaring heights, magnificently embellished interiors and exteriors, elaborate lighting and sheer grandeur on a massive scale.

The Doges Palace in Venice, Italy (pictured below) housed the political aristocracy of the Republic of Venice for a thousand years. Built in 1309 CE, its rhythmic levels of columns and pointed arches, divided by fractals as they rise, give way to elaborate geometric patterns in the pink brick façade. The ornamental additions at the top edge reinforce the patterns below.

The Doges Palace, 1309 CE, viewed from St. Mark’s Square, Venice, Italy. Image by Martti Mustonen and licensed through Creative Commons.

ARCHITECTURE IN CHINA & THE FAR EAST

Chinese architecture refers to a style of architecture that has taken shape in East Asia over many centuries. The structural principles of traditional Chinese architecture have remained largely unchanged. Chinese architectural (and aesthetic) design is based on symmetry, a general emphasis on the horizontal and site layouts that reflect a hierarchy of importance. These considerations result in formal and stylistic differences in comparison to the West, and display alternatives in design.

The Chinese have used stone, brick and wood for centuries. The Great Wall, begun in the 5th century BCE, was intended to keep nomadic invaders out of Northern China. The stone wall covers 5500 miles in its entirety. The rigid material takes on a more flexible appearance as it conforms to the contours of the landscape surrounding it.

CROSS-CULTURAL INFLUENCES

As overland and marine trade routes expanded between Eastern and Western civilizations so did the influence of cultural styles in architecture, religion and commerce. The most important of these passages was the Silk Road, a system of routes that developed over hundreds of years across the European and Asian continents. Along this route are buildings that show cross-cultural influences in their design.

The Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem offers different cultural influences manifest in one building: a classic Greek colonnade at the main entrance, the gold dome and central turret supporting it, western style arches and colorful Islamic surface embellishment.

The Dome of the Rock, on the Temple Mount, in the Old City of Jerusalem, Photo Credit Andrew Shiva, Image licensed through

Creative Commons

The Louvre Palace in Paris, once the official royal residence and now one of the world’s biggest museums, had its beginnings in the 12th century but didn’t achieve its present form until recently. The building’s style is French Renaissance – marked by a formal symmetry, horizontal stability and restrained ornamentation. The Louvre executive board chose architect I. M. Pei’s glass pyramid design as the defining element for the new main entry in 1989. The choice was a great success: the pyramid further defines the public space above ground and gives natural light and a sense of openness to the underground lobby beneath it.

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

Beginning in the 18th century the Industrial Revolution made fundamental changes in agriculture, manufacturing, transportation and housing. Architecture changed in response to the new industrial landscape. Prior to the late 19th century, the weight of a multistory building had to be supported principally by the strength of its walls. The taller the building, the more strain this placed on the lower sections. Since there were clear engineering limits to the weight such load-bearing walls could sustain, large designs meant massively thick walls on the ground floors, and definite limits on the building’s height.

Eiffel Tower, Start of construction of second stage, May 1888. Image in the public domain

Forged iron and milled steel began to replace wood, brick and stone as primary materials for large buildings. This change is encapsulated in the Eiffel Tower, built in 1889. Standing on four huge arched legs, the iron lattice tower rises narrowly to just over 1000 feet high. The Eiffel Tower not only became an icon for France but for industry itself – heralding a new age in materials, design and construction methods.

In America, the development of cheap, versatile steel in the second half of the 19th century helped change the urban landscape. The country was in the midst of rapid social and economic growth that made for great opportunities in architectural design. A much more urbanized society was forming and the society called out for new, larger buildings. By the middle of the 19th century downtown areas in big cities began to transform themselves with new roads and buildings to accommodate the growth. The mass production of steel was the main driving force behind the ability to build skyscrapers during the mid 1880s.

Steel framing was set into foundations of reinforced concrete, concrete poured around a grid of steel rods (re-bar) or other matrices to increase tensile strength in foundations, columns and vertical slabs.

MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE

The move to modernism was introduced with the opening of the Bauhaus school in Weimar Germany. Founded in 1919 by the German architect Walter Gropius, Bauhaus (literal translation “house of construction”) was a teaching and learning center for modern industrial and architectural design. Though not a movement or style in itself, Bauhaus instructors and staff reflected different artistic perspectives, all of them born from the modern aesthetic. It was partly the product of a post- World War I search for new artistic definitions in Europe. Gropius’s commitment to the principle of bringing all the arts together with a focus on practical, utilitarian applications. This view rejected the notion of “art for art’s sake”, putting a premium on the knowledge of materials and their effective design. This idea shows the influence of Constructivism, a similar philosophy developed concurrently in Russia that used the arts for social purposes. Bauhaus existed for fourteen years, relocating three times, and influencing a whole generation of architects, artists, graphic and industrial designers and typographers.

In 1924 Gropius designed the Bauhaus main building in Dessau. Its modern form includes bold lines, an asymmetric balance and curtain walls of glass. It’s painted in neutral tones of white and gray accented by strong primary colors on selected doors.

Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, 1925-26, Image in public domain

Frank Lloyd Wright is considered one of the 20th century’s greatest architects. Wright designed buildings, churches, homes and schools, but is best known for his design of Falling Water, a home in the Pennsylvania countryside for Chicago department store owner Edgar Kaufman. His design innovations include unified open floor plans, a balance of traditional and modern materials and the use of cantilevered forms that extends horizontal balance.

The Guggenheim Museum in New York City is an example of Wright’s concern with organic forms and utilization of space. The main element in the design is a spiral form rising from the middle of the cantilevered main structure. Paintings are exhibited on its curved walls. Visitors take the elevator to the top floor and view the works as they travel down the gently sloped hallway. This spiral surrounds a large atrium in the middle of the building and a domed skylight at the top.

Atrium, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Manhattan, New York, 1959, Image in the public domain

POST MODERN & CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE

Postmodern architecture began as an international style whose first examples are generally cited as being from the 1950s, but did not become a movement until the late 1970s and continues to influence present-day architecture. Postmodernity in architecture is generally thought to be heralded by the return of “wit, ornament and reference” to architecture in response to the formalism of the International Style.

Michael Graves’s Portland Building from 1982 personifies the idea behind postmodernist thought. A reference to more traditional style is evident in the patterned column-like sections. Overt large-scale decorative elements are built into and onto the exterior walls, and contrasts between materials, colors and forms give the building a graphic sense of visual wit.

We can see how architecture is actively evolving in the contemporary work of Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid. Gehry’s work is famous for its rolling and bent organic forms. His gestural, erratic sketches are transformed into buildings through a computer aided design process (CAD). They have roots in postmodernism but lean towards a completely new modern style. They have as much to do with sculpture as they do with architecture. Seattle’s Experience Music Project is an example of the complexity that goes into his designs. Its curves, ripples and folds roll across space and the multi-colored titanium panels adorning the exterior accentuate the effect.

GREEN ARCHITECTURE

In the last decade there has emerged a strong interest in developing “green” architecture – designs that incorporate ecologically and environmentally sustainable practices in site preparation, materials, energy use and waste systems. Some are simple: buildings oriented to the south or west helps with passive solar heating. Others are more complex: Solar voltaic cells on the roof to generate power to the building. Green roofs are made of sod and other organic material and act as a cooling agent and recycle rainwater too. In addition, technological innovations in lighting, heating and cooling systems have made them more efficient.

A branch of the Seattle Public Library uses green design. A glass curtain wall on the north side makes use of natural lighting. Overhanging wooden roof beams shades harsh light. The whole structure is nestled under a green roof of sod and over 18,000 low water use plants. Seven skylights on the roof provide more natural lighting.

Time-Based Art

Explain the techniques of film and video art

Learning Activities

The learning activities for this section include:

- Reading: Time-Based Media: Film and Video

Take time to review and reflect on this activity in order to improve your performance on the assessment for this section.