Adapted by Denise Cummings-Clay

Conditions of Use:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Chapters derived from:

https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/music-and-the-child

by Natalie Sarrazin

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License.

Click on the printer icon at the bottom of the screen

![]()

Make sure that your printout includes all content from the page. If it doesn't, try opening this guide in a different browser and printing from there (sometimes Internet Explorer works better, sometimes Chrome, sometimes Firefox, etc.).

If the above process produces printouts with errors or overlapping text or images, try this method:

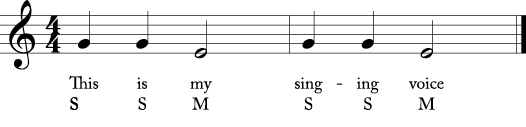

Chapter Objective: One of the most basic yet challenging activities to do with children is to teach them a song.This chapter focuses on the child’s singing voice, including their vocal range, selection of appropriate musical material, and methods for teaching a song in a musically meaningful, cognitively stimulating way that lays the groundwork for future integration.

One common mistake that adults make when singing with children is that they tend to “pitch” the songs, (or sing them in a key), that is comfortable for themselves, but unfortunately, out of a comfortable singing range for the children. Adults sing in much lower range than children, therefore pitching a song too low causes children to be unsuccessful at reaching some of the lower notes.

Pitching a song in the wrong range can have significant negative consequences on a child’s musical self-esteem. An incorrect key can take away the child’s ability to sing the song well or sing the song at all. Singing in a key that is out of a child’s range would be analogous to an art teacher giving a creative assignment to students and then placing all of the art materials up on a shelf out of reach for most of them. While a few might be tall enough, most won’t be. After a while, they will give up trying to reach the material altogether. Similarly, these are the students who start to believe that they can’t sing at all, and give up on music.

Although we are used to hearing and singing pop music, a child’s voice is not yet ready to sing songs either with such a wide vocal range or with the sophisticated vocal styling or timbre that he or she might try to imitate from pop singers. As children’s voices are very light, they should not be pushed out of their vocal ranges too soon. Using a clear, clean, straight head voice rather than chest voice will help to avoid this, and will strengthen a child’s vocal musculature for a lifetime of excellent singing.

One good habit to help children sing well is to ask them sing in their head voice rather than their chest voice. Although most songs children hear are pop songs that are placed in the chest, a child’s voice is not yet developed, and should not be belting out or pushing from the lower range or chest voice. Head voice requires placing the sound higher up in the “vocal mask” or the face, as if singing from the eyes. Chest voice feels like the sound is emanating from the chest, which tends to create a lot of tension in the throat, particularly in younger singers. The head voice is lighter, more tension-free, and more natural and therefore more beautiful sounding.

Below are the general ranges of a child’s voice.

The strongest notes in a child’s vocal range are right in the middle of their range, around pitches F and G. While they may be able to hit higher or lower notes, these few notes are where they can sing the loudest and most comfortably.

Activities for helping children explore their voices and find their head voice:

Activities for exploring the child’s voice and finding the child’s head voice:

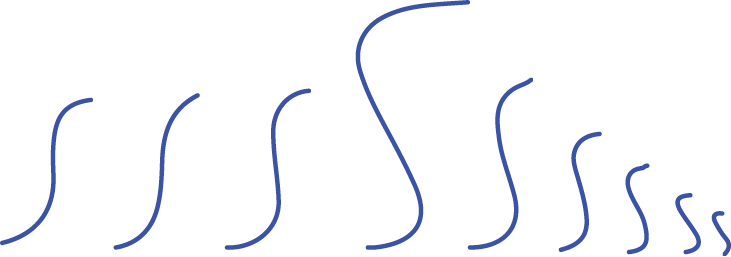

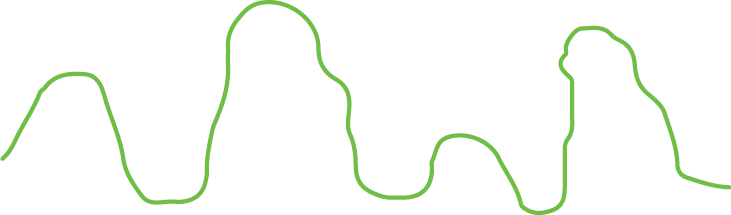

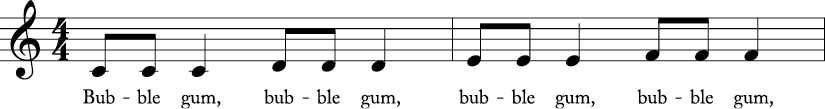

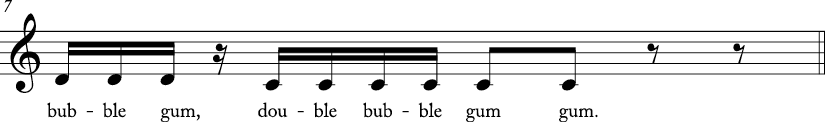

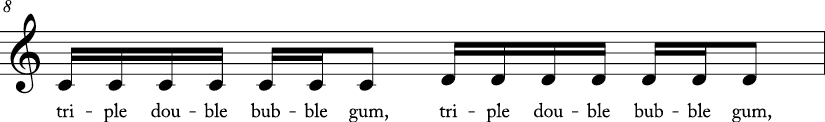

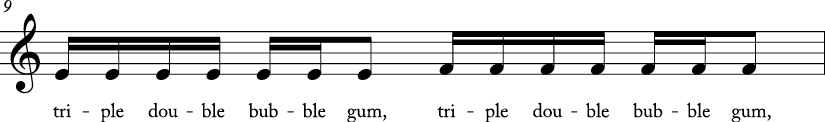

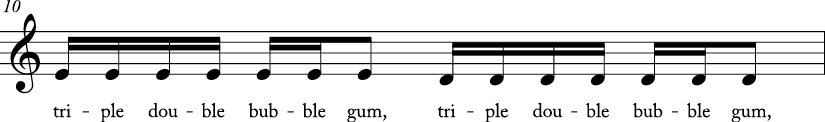

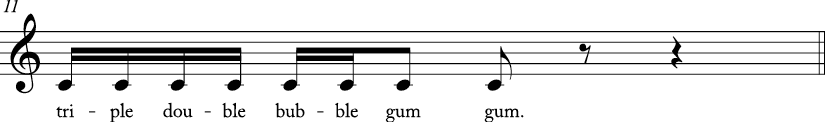

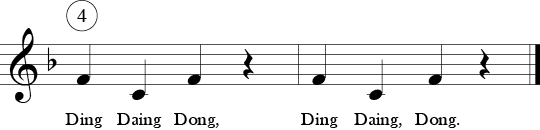

Abstract notation: Example 1

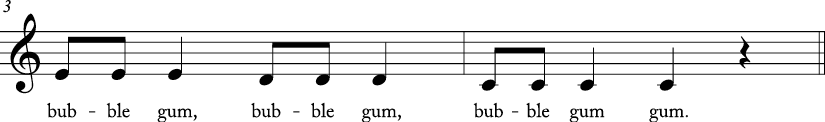

Abstract notation: Example 2

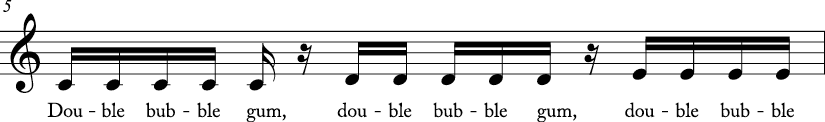

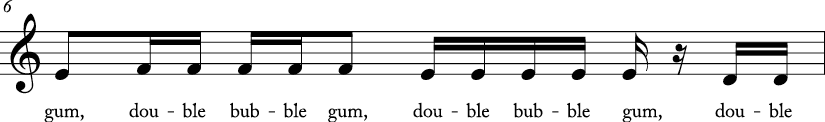

Abstract notation: Example 3

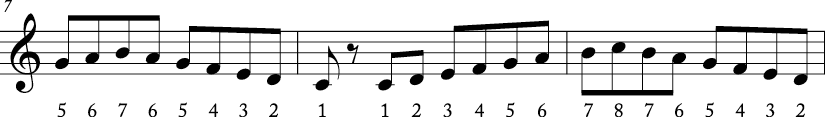

Doing warm-ups not only helps children explore their vocal range but expand it as well. As with all pitched warm-ups, start at the bottom of the range and move up in half-step increments and then back down. Some of the warm-ups are quite cognitively challenging.

This is a cognitively challenging exercise. The easiest way to sing it is to write the pattern for the exercise on the board, telling students that each number corresponds to a note on the major scale (1 = middle C, 2 = D, etc.). After singing from a low C to a high C, reverse the pyramid, and begin and high C and descend downward (i.e. 8, 878, 87678).

1 1

1 2 1

1 2 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 5 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

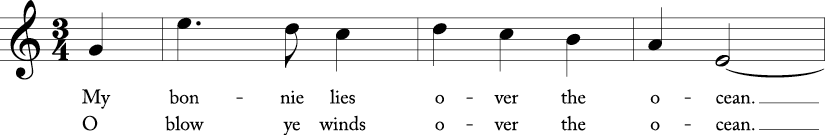

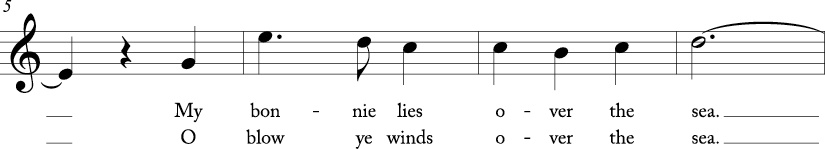

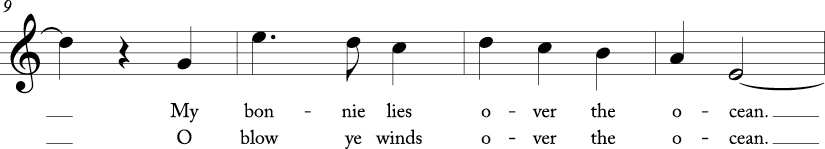

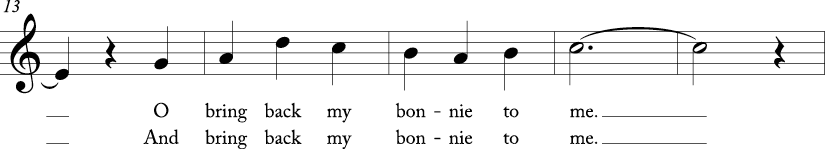

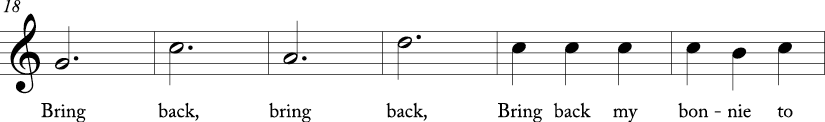

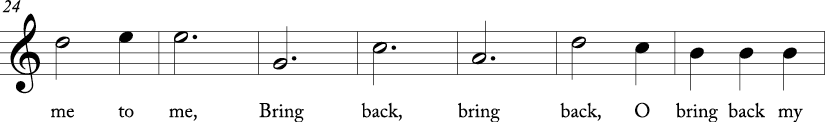

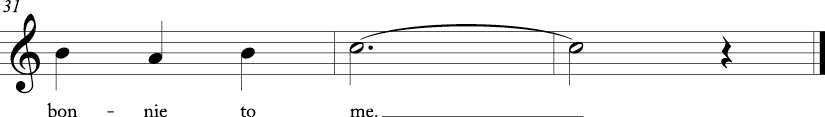

Children are certainly capable of singing very complicated rhythms and melodies just by listening and aural imitation, but when selecting a song to sing, it is important to find a song that matches the vocal range and the tessitura of the children. A song’s range concerns all of the notes in a song from lowest to highest, while the tessitura concerns the part of the register that contains the most tones of that melody. For example, you might have a song with a few pitches that are too high or too low for the child’s voice, but the majority of the song lies within a proper singing range for the child. Consider the 1857 song “Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush.” The song contains a few notes on middle C, which is a bit low for young children, but the tessitura of the entire song contains notes from F to a C’, all of which are easily accessible. The traditional Scottish folk song “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean” has a range of an entire octave from C to C’, but most of the song lies within a Major 6th from E to C’.

After finding songs with the appropriate range and tessitura, it is critical to analyze a few additional musical components before you teach it. The important things to assess are: the song’s meter and then the phrases and sections of the song. The final step is to have the song down cold before attempting to teach it. The same goes for any material you want to teach children. If you yourself don’t really know it, you will not be able to teach it successfully.

If the song is notated, you can just look on the music to find the meter (e.g. 2/4, 3/4, 4/4, 6/8, etc.). However, if you don’t have the song written in notation, you will need to determine the song’s meter by ear. To find a song’s meter, first find the downbeat (the strongest beat) and the weaker beats of each measure. Begin tapping on a desk while singing the song. If you tap slightly harder on the downbeat (the first beat of the group of two or three or six in each measure of the song) and begin singing, it will help you to find the meter. Groups of beats in Western music are mostly either in duple (two or four beats for a measure) or triple (three or six beats in a measure), so try tapping in groups of two first to see if that fits, and then try three.

For example, consider the song “Take Me Out to the Ballgame.” Is it in duple or triple meter?

|

Sing and tap: |

1 2 > |

1 2 > |

1 2 > |

1 2 > |

|

Then try: |

1 2 3 > |

1 2 > |

3 1 |

2 3 > |

Which meter fits the song better? The first is in duple, the second is in triple feel. The triple feel probably feels better—as it should because the song is in a 3/4 meter. In addition to the downbeat and meter, you will also need to determine whether the first note of the song begins directly on the downbeat or on a pickup. Songs that begin on a pickup (i.e., a note that is not on the first beat of the measure) are more difficult and require a stronger preparation from the teacher (for examples of this, see the section “Prepare” on page 104.)

Children’s songs are usually simple in form, often containing only one or two sections or parts; A one-part song (unitary) is designated with the letter A for purposes of analysis, while two-part songs (AB) are referred to as binary, verse-refrain, or verse-chorus. Songs in which the first section returns again at the end are known as ternary, three-part or ABA.

|

Activity 5A Try this Now try singing and tapping each line above while singing “Old MacDonald Had a Farm.” Which meter best fits the song? Think of some other children’s songs you know and sing them to find which meter is most appropriate. |

While it may seem quite intuitive to teach a song to children, there’s actually a great deal to consider. The different ways to teach a song are related to children’s different learning styles, such as aural and visual learning, and the child’s appropriate cognitive development; e.g., age and grade development. The first method is to teach a song by rote, a technique also known as aural learning, or “by ear.” Rote usually requires a great deal of repetition. The second method is a hybrid known as rote-note, where the song is taught mostly by ear, but also involves the addition of some type of visual element, such as showing some notation. The third method is known as note, which is teaching the song using written in notation (e.g. sheet music). These three styles of teaching not only relate to aural and visual learners, but also correlate to the basic cognitive development theories of Jerome Bruner’s modes of representation and Jean Piaget’s four stages of cognitive development.

Song Teaching Style |

Primary Learning Style |

Developmental Level |

Bruner |

Piaget |

|

Rote/Aural Teaching (Sing by ear, no notation) |

Aural |

Any age, but appropriate for early childhood |

Enactive (action-based) |

Sensorimotor (learning through senses) |

|

Rote-Note Teaching (Mostly aural, partial notation) |

Aural-Visual |

Appropriate for lower elementary students (K–2) |

Iconic (image-based) |

Pre-Operational |

|

Note Teaching (Teaching a song through written notation) |

Visual |

Appropriate for upper elementary (3–6) |

Symbolic (language-based) |

Concrete Operational |

Rote/aural teaching is enactive (action-based) and can be used at any age through adulthood, but is particularly appropriate for preschool through early childhood (into the lower elementary grades). Motor skills can be added to a song to increase the learning dimensions.

Rote-note teaching is partially iconic (image-based) and appropriate for lower elementary students (K–2) just learning to read as it involves some type of iconic or image-based representation of music, such as using abstract notation or modified rhythmic or pitch notation.

Note teaching is symbolic (language-based) and more appropriate for upper elementary grades.

The next decision is whether to teach the song as a whole or by one phrase or line at a time. This consideration will happen regardless of which teaching style—rote, rote-note, or note—is used. Note that the term phrase refers to the music, while line refers to the lyrics or poem.

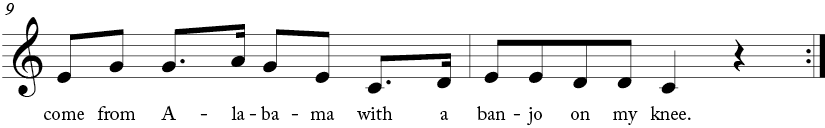

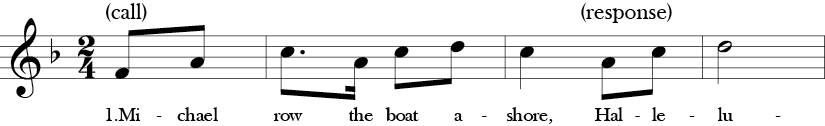

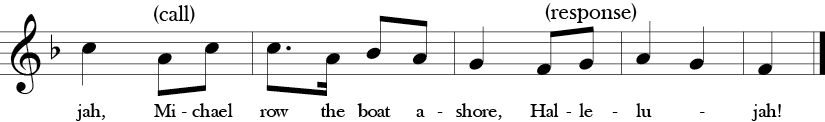

Whole song: Teaching a whole song is exactly what it sounds like…singing the whole song at once and having the students echo the whole song right back. This is good for very short, simple songs; songs that have a lot of repetition either in the words or music; or call and response songs with few variables. The benefit of this is, according to Edwin Gordon’s approach, to have the child experience the whole piece first, and then learn what the song comprises in detail.

Phrase-by-phrase teaching is best when the song is longer or has a lot of lyrics or complex melodies. This is the most common method for teaching more complicated or lengthy songs. In this technique, each phrase is sung by the teacher and then immediately echoed back by the students.

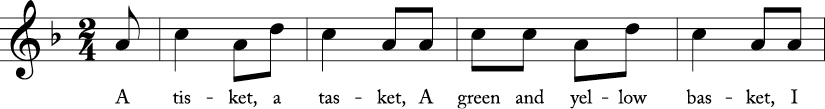

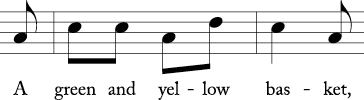

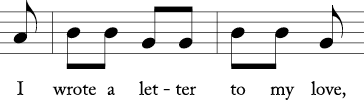

For example, consider the song “A Tisket, a Tasket”:

American children’s game song, late 19th century

Teacher: A tisket, a tasket

Students: A tisket, a tasket

Teacher: A green and yellow basket

Students: A green and yellow basket

Teacher: I wrote a letter to my love

Students: I wrote a letter to my love

Teacher: And on the way I dropped it

Students: And on the way I dropped it

If there is more than one verse to a song, after teaching one verse, make sure to repeat the first verse several times with the students before moving on to the next verse.

|

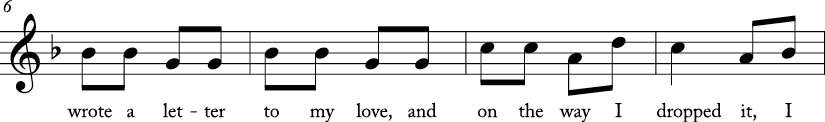

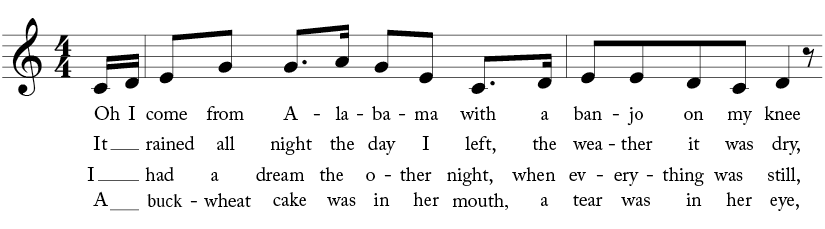

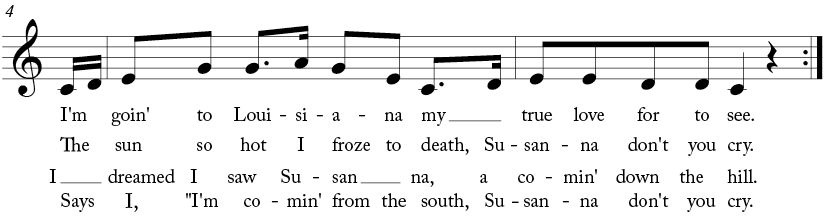

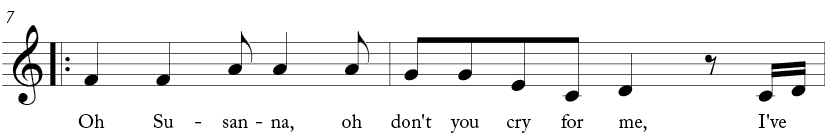

Activity 5B Try this You are teaching a group of kindergarteners. Which songs would you be more likely to teach 1) as a whole song; 2) phrase by phrase?

|

Traditional children’s song, 17th century

American minstrel song, Stephen Foster, 1848

African American spiritual, South Carolina Sea Islands, 1860s

Of course singing a song is fun, but it can also be highly educational. In preparation for integration, and for using music with other art and subject areas, train yourself to explore the full potential of each song.

Having students identify or “analyze” what is going on in the song is educationally sound and cognitively effective. They are listening, analyzing, visualizing, sequencing, and applying concentrated brainwork to understand what they are singing.

When most people think about “song” they tend to think of the lyrics plus the music together, and often don’t realize that the music is a separate entity with its own cohesiveness and structure. Getting students to understand the musical differences between phrases is actually less challenging than you might imagine. For example, if I asked you which lines of “A Tisket, A Tasket” are the same, you would say none if you thought of only the lyrics. But what if I asked you which musical phrases are the same? If you have trouble, remove the lyrics and hum the melody. Now how many are the same? Three of them—the first, second, and fourth. For example, the melody for “A Tisket, A Tasket” looks like this, with lines 1, 2, and 4 being basically the same. Line 3 is different.

Having students hum the melody rather than singing words helps them hear the melody separately from the lyrics. Holding up fingers as they sing each phrase marks where they are in the song. Better still, have them sing the solfege for the different lines instead of the words or humming. In terms of analysis, solfege instantly informs the listener or singer which lines of music are the same and helps them compare and contrast each line rather quickly!

While many children’s songs are relatively easy to sing, most will need to be broken down into smaller parts (phrases) to learn easily. Breaking a song into “chunks” helps exercise children’s cognitive and analytical abilities to understand, compare, and contrast the different parts or phrases of a song. Below are some important strategies for teaching a song either for the first time, or even to review a song or help children analyze an old and familiar song.

Imagine that you are at the beginning of a track race. You are at the starting gate, and are anxiously waiting for the signal to begin running. You hear a count, then a starting shot, and you’re off. Now imagine you are at a race in which no count or starting signal is given, but a chosen leader just decides to start running and you are expected to jump in and catch up. In some ways, beginning a song is similar. Many adults begin a song with no preparation and expect children to just jump in, requiring children to figure out the tempo, the starting pitch, and the lyrics all at the same time, and on their own.

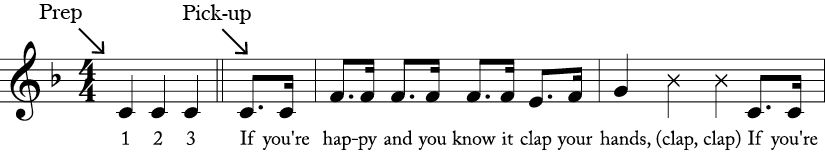

It takes just a few seconds to prepare students before they begin a song. Counting them in gives them the tempo, and singing the counts on the opening pitch gives them the starting note. Below are a few hints for starting a song that will help students be successful right from the first note!

The pulse indicates the tempo at which you would like to sing the song, as well as the song’s meter.

Find the starting pitch for the song on any pitched instrument (i.e., piano, xylophone, recorder, or pitch pipe). Keep in mind the child’s vocal range and the range/tessitura of the song.

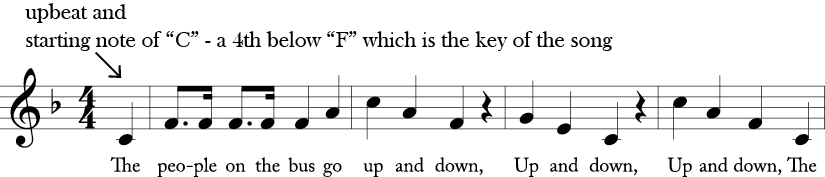

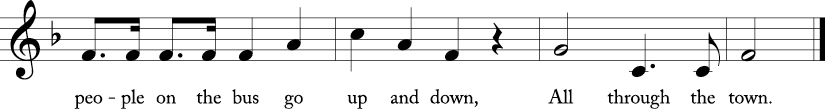

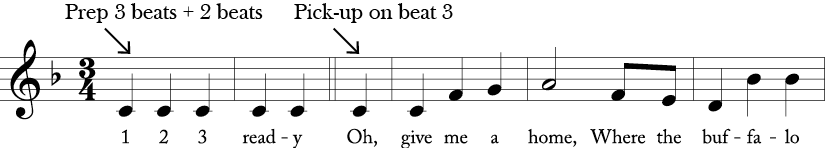

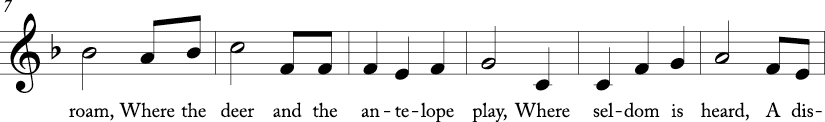

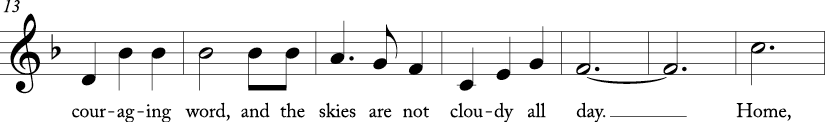

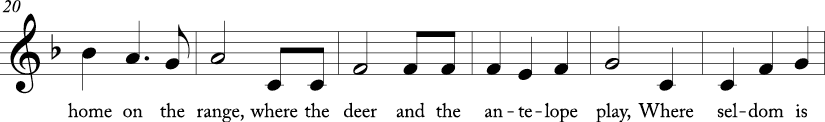

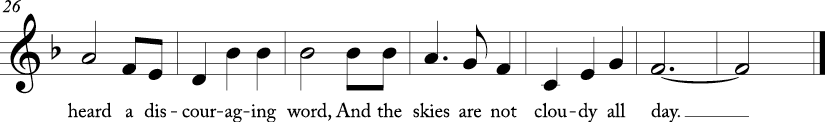

When bringing in the children to sing, you need to be aware of whether or not the song begins on a downbeat or upbeat (aka pickup). Many songs begin directly on the downbeat such as “Jingle Bells” or “Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush,” while others such as “Oh, Susanna!” or “The People on the Bus Go Up and Down” begin with an upbeat or pickup (see below).

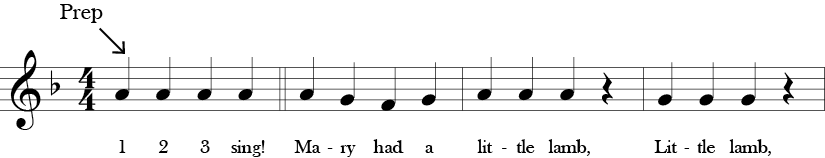

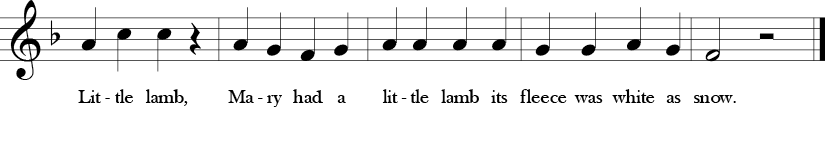

Now you have to take all of the above information and somehow transmit it to the children before you sing. Develop a preparatory phrase that you feel comfortable with which gives children the pulse and pitch of a song. The following preparations work very well for songs in duple meter if you sing them on the starting pitch that you want the children to come in on.

For duple meter (2/4 or 4/4) songs:

|

| | | | 1-2-3 sing |

|

| | | | | 1-2 here we go |

|

| | | | | Ready and sing now |

For triple meter (3/4 or 6/8) songs:

|

| | | | | | 1-2-3 | 1-2-sing |

|

| | | | | | Here we go | read-y now |

Add a pointing motion to start them off, such as an arm or hand gesture that lets them know it is their turn to sing. Use this same gesture when echoing during the phrase-by-phrase method to help students enter at the right time.

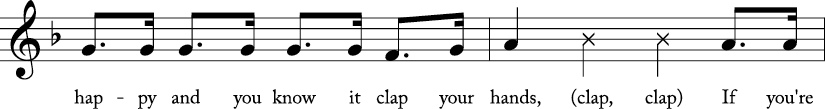

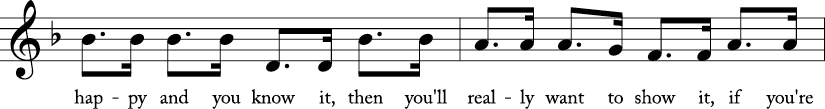

Below are some examples of preparations to sing a few well-known songs.

Daniel E. Kelley

|

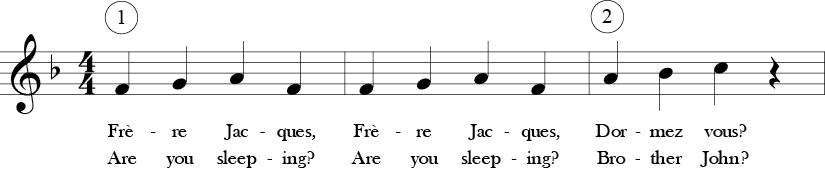

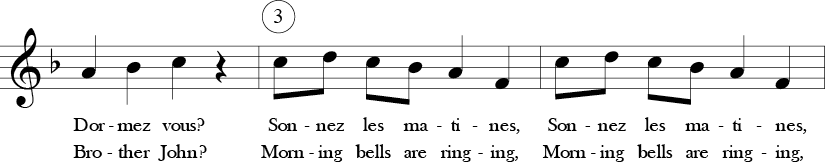

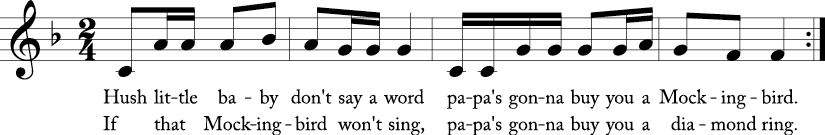

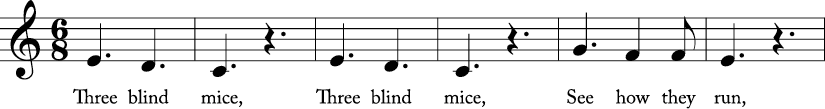

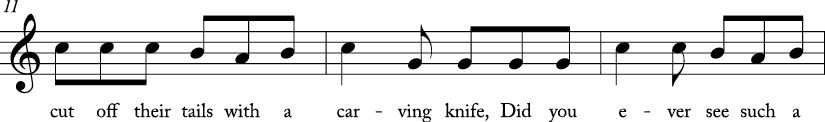

Activity 5C Try this How would you prepare students to begin singing the following songs? What is your starting pitch? Meter? Tempo? Is there a pick-up/upbeat?

|

French folk round, 18th century

American lullaby song

English children’s song attributed toThomas Ravenscroft, 1609

aural learning: learning music “by ear”—learning by hearing only (no use of written notation)

beat: a pulse in a piece of music; the basic unit of time in music

binary form: a song in with two discernible sections; also referred to as verse-refrain or verse-chorus and designated as AB.

chest voice: singing when the sound feels like it is emanating from the chest or throat

downbeat: the first beat in the measure; beat in a measure that is most accented

duple: two or four beats per measure

head voice: placing the sound higher up in the “vocal mask” or the face, as if singing through the eyes

line: reference to a line of the lyrics or poem when learning music; usually corresponds to a musical phrase

note: learning music by reading the notes; reading the music or score in order to play or learn

note-rote: song is taught mostly by ear or repetition, but also shows some iconic notation (written notation)

phrase-by-phrase: teaching a song one line at a time; breaking down the song into individual phrases

pickup: a note or series of notes that preceded the first downbeat of the first measure; also called anacrusis

pitch: the frequency of the sound based upon its wavelength; the higher the pitch, the higher the frequency

pulse: in learning music, the pulse indicates to the children the tempo at which you would like to sing the song as well as the song’s meter; “feel the beat”

range: all of the notes in the song from lowest to highest

rote: learning through repetition; learning without use of written music or a score

song phrase: reference to a group of notes in learning music, usually equivalent to a sentence or the length of one line of poetry

tempo: pace in which the notes of a song are sung or played

ternary form: as song with 3-sections, where the first section returns at the end in exact form and the middle section is different or contrasting; designated as ABA.

tessitura: the part of the register in which most of the tones of the melody or voice part lies

triple: three or six beats per measure

unitary: a song with only one section, and no refrain; can be labeled as A.

upbeat: pickup beat (see above)

verse-refrain: a verse corresponds to a poetic stanza of a song; usually distinguished from the chorus or refrain of a song, which has repeated lyrics (e.g., in “Oh, Susanna” the verse begins with “oh I came from Alabama” and the chorus or refrain begins with “Oh, Susanna, oh don’t you cry for me…”)

whole song: teach the whole song at once without breaking it into individual phrases; useful technique for very short songs

Library Info and Research Help | reflibrarian@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4215

Loans or Fines | circ@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4222

475 Grand Concourse (A Building), Room 308, Bronx, NY 10451