Adapted by Denise Cummings-Clay

Conditions of Use:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Chapters derived from:

https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/music-and-the-child

by Natalie Sarrazin

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 4.0 License.

Click on the printer icon at the bottom of the screen

![]()

Make sure that your printout includes all content from the page. If it doesn't, try opening this guide in a different browser and printing from there (sometimes Internet Explorer works better, sometimes Chrome, sometimes Firefox, etc.).

If the above process produces printouts with errors or overlapping text or images, try this method:

Chapter Summary: This chapter focuses on the role of music in early childhood, including the importance of musical experience in early childhood, the musical abilities and enjoyment of infants and children, and the vocal ranges of the young child. It also explores musical activities and repertoires appropriate for young children.

What a child has heard in his first six years of life cannot be eradicated later. Thus it is too late to begin teaching at school, because a child stores a mass of musical impressions before school age, and if what is bad predominates, then his fate, as far as music is concerned, has been sealed for a lifetime.

—Zoltán Kodály, Children’s Day Speech, 1951

How important are the arts as a mode of expression for children? Children, especially very young children, cannot express themselves fluently either through speech or writing—two modes of communication that adults use almost exclusively. Instead, children express themselves through movement, sound, and art. If they can express themselves through these modes, it is logical that they can learn through them as well.

Many times, however, adults are at a loss to understand or interpret what it is children are saying to us, or to appreciate how profound it might be. Mark E. Turner (2008), building upon the work of Edwin Gordon and Reggio Emilia, thought considerably about children’s representation through the arts. He sought to provide authentic ways for children to express themselves and developed scaffolding to better harness and understand children’s musical development. As Turner states, the idea that the “performing arts” must always be performed onstage to be valid detracts from their use to develop and explore the emotional, cognitive, social development and human potential.

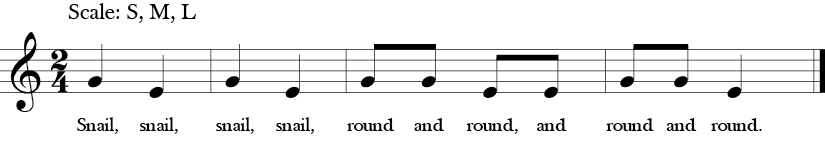

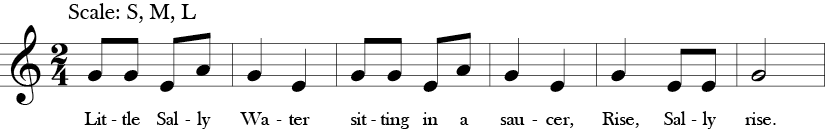

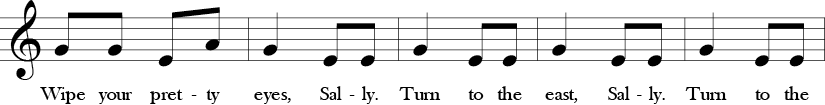

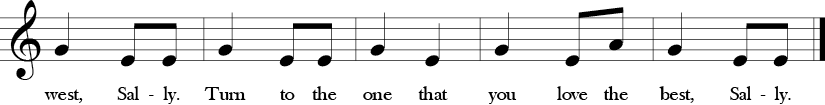

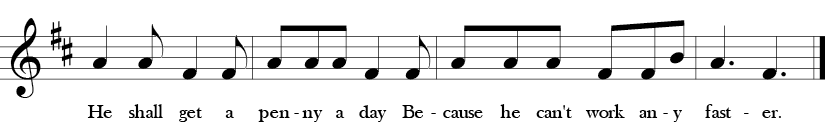

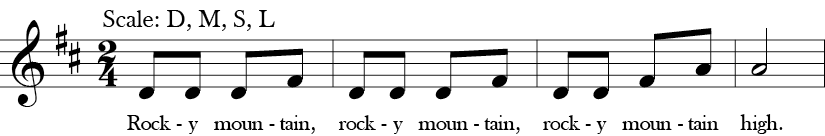

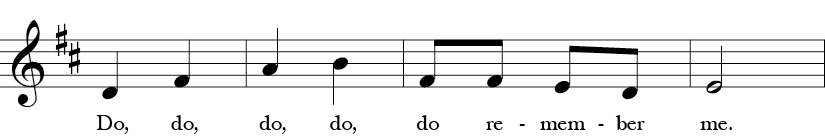

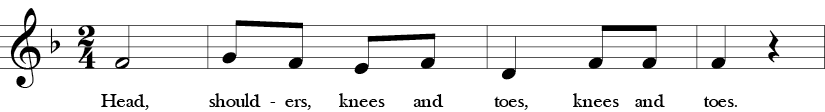

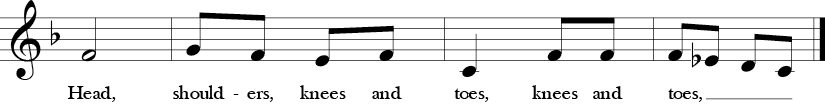

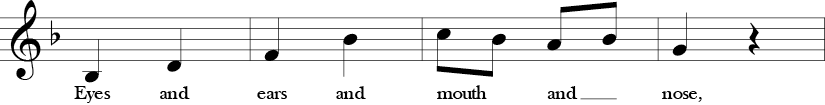

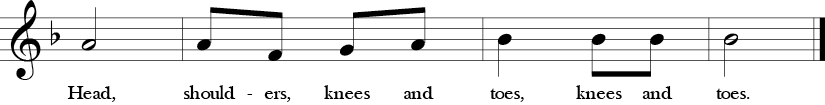

Any of the music methods (e.g., Kodály, Orff) mentioned in Chapter 4 offer sequential learning for children. Kodály in particular spent a great deal of effort on developing beautiful singing voices for young children. Children’s voices, after all, are their first instrument—a child’s first exceptionally pleasant musical experience is likely to be hearing lullabies from a parent or guardian, and then vocally experimenting with his or her own voice. Kodály graded learning in small steps for the very beginner learners, starting with three-note songs (sol, mi, la) and expanding gradually to four, five, and six notes and beyond. For the youngest, songs with three notes are an excellent place to start, because these children will not have much difficulty imitating or matching these pitches and can be successful from the outset.

Music activity for infants and toddlers engages the child’s aural and physical being. Such age-old activities include tickling, wiggling, bouncing, and finger playing.

At this level, musical play creates and reinforces the special personal bond between an adult (or older child) and infant, while also introducing music to the child. For newborns and very young children, speaking a rhyme and wiggling toes connects sound to a pleasurable and intimate act, as well as introducing the idea of rhythm and phrasing to newborns and young children.

Below are a few of the rhymes and songs particularly good for newborns and toddlers. They include some very familiar nursery rhymes and action games appropriate for this age group. Keep in mind that almost any nursery rhyme can be used for these activities, as long as they have a steady beat, which luckily most of them do.

For newborns to three-year-olds, having them feel the beat in their bodies, aided by adults, are called “bounces,” based on the experience of bouncing a child up and down on a knee or lap.

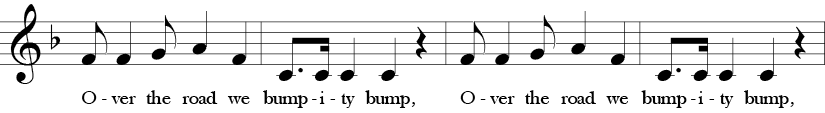

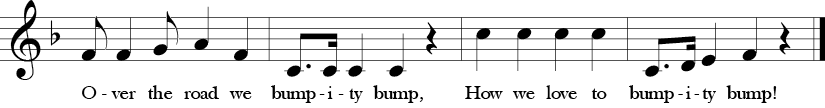

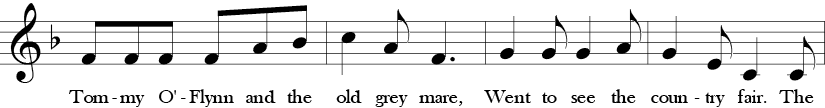

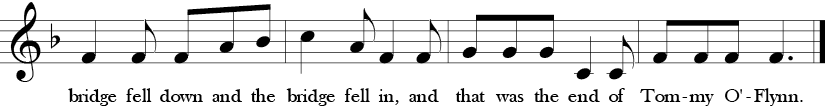

Tommy O’Flynn and the old grey mare (bounce child on knees)

Went to see the country fair

The bridge fell down and the bridge fell in (open knees and let child drop a bit)

And that was the end of Tommy O’Flynn

Wiggles are those activities involving the wiggling of fingers or toes. “This Little Piggy Went to Market” is another wiggle with which you may be familiar.

The first little pig danced a merry, merry jig

The second little pig ate candy

The third little pig wore a blue and yellow wig

The fourth little pig was a dandy

The fifth little pig never grew to be big

So they called him Tiny Little Andy

Tickles involve exactly that—tickling the child either all over or just in the stomach, usually ending in lots of giggles!

Slowly, slowly, very slowly up the garden trail (crawl hands up baby starting from feet)

Slowly, slowly, very slowly creeps the garden snail (continue crawling)

Quickly, quickly, very quickly all around the house (tickle all over)

Quickly, quickly, very quickly runs the little mouse (continue tickling)

My father was a butcher (make chopping motions on child’s body)

My mother cuts the meat (make cutting motions on child’s body)

And I’m a little hot dog

That runs around the street (tickle all over)

Pizza, pickle, pumpernickel (flash one hand wide, then the other, then roll arms)

My little one shall have a tickle! (tickle child)

One for your nose (tickle child’s nose)

And one for your toes (tickle child’s toes)

And one for your tummy, where the hot dog goes! (tickle child’s tummy)

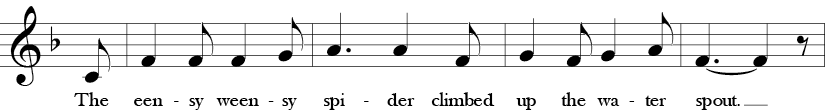

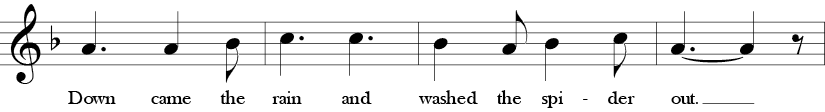

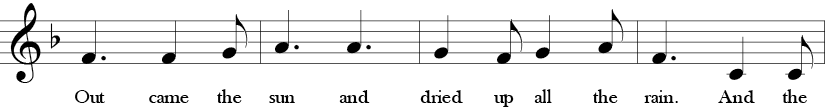

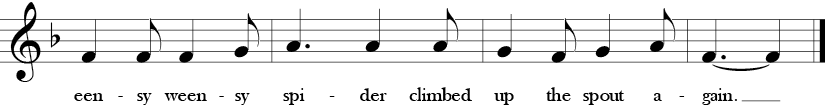

Finger play songs can also be types of tickles. The most common finger play song is the “Eensy, Weensy Spider.”

For an infant, the parent would take the child’s foot or hand and tap it to the beat of the music. If the child can tap by him- or herself, that will work also.

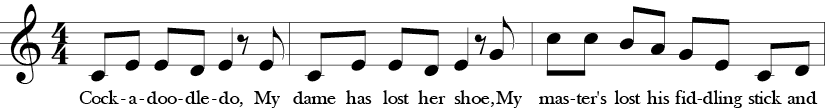

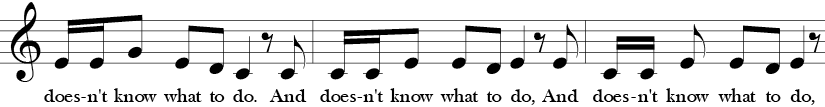

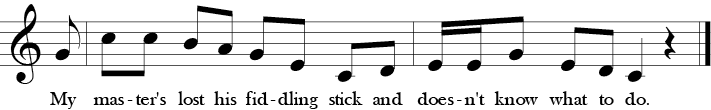

English nursery rhyme, 1765

Cock-a-doodle doo (tap one foot)

My dame has lost her shoe

My master’s lost his fiddling stick

And doesn’t know what to do.

Cock-a-doodle doo (tap other foot)

What is my dame to do?

Til master finds his fiddling stick

She’ll dance without a shoe.

Cock-a-doodle doo (tap both feet)

My dame has found her shoe

And master’s found his fiddling stick

Sing doodle, doodle, doo.

As children develop physically, they can clap their hands either together or against those of another. The well-known “Patty Cake” is a good example.

Patty cake, patty cake, baker’s man

Bake me a cake as fast as you can

Roll it and pat it and mark it with a “B”

And put it in the oven for baby and me!

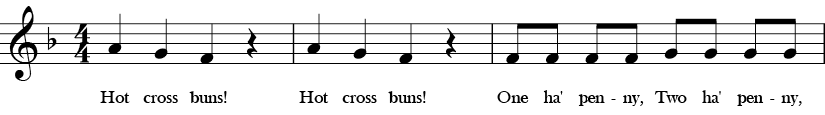

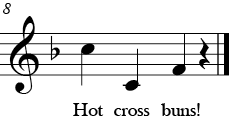

Hot cross buns

Hot cross buns

One a penny, two a penny

Hot cross buns.

Pease porridge hot

Pease porridge cold

Pease porridge in the pot

Nine days old.

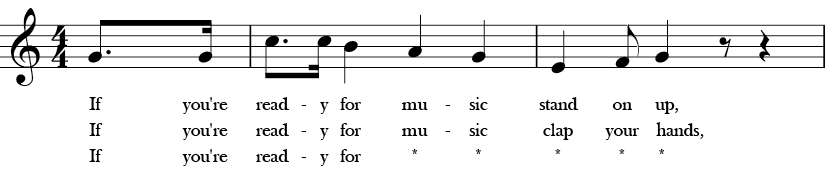

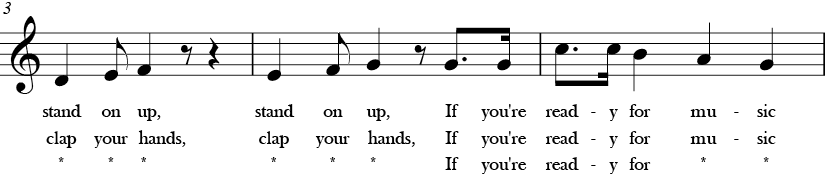

Responding to a musical beat is an innate part of what it means to be human, and even the youngest children can begin to feel music, either by moving to the beat or having an adult help a child move to the beat (Feierabend, 2001).

The simplest thing to do is to find recordings of quality music and play songs with an even, steady beat and have children move, clap, tap, patsch, hit an instrument, or walk to that beat.

An extended possibility is to create a story, miming movements that reflect a steady beat while telling a simple narrative. For example, a leader begins by miming actions such as teeth brushing, bouncing a ball, or eating food from a bowl, and the group imitates them. All movements are done to the beat (e.g., teeth brushing, up down up down). At the end of the leader’s turn, the children have to remember the “storyline.”

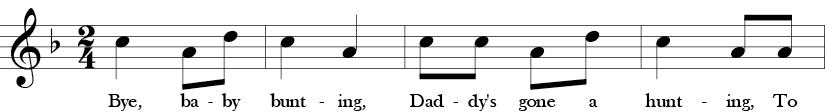

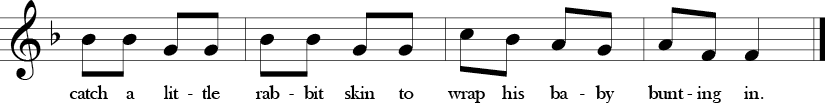

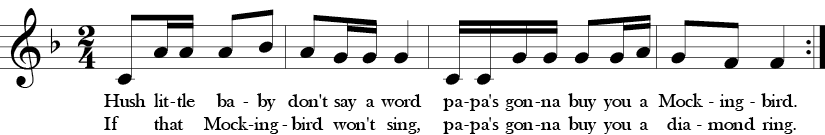

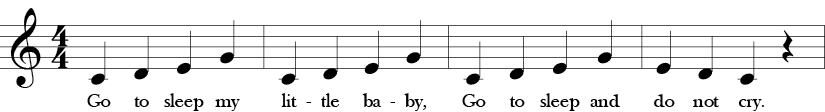

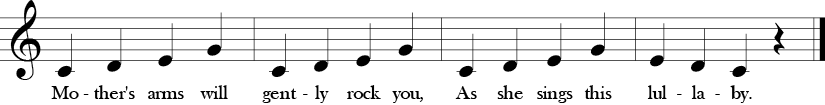

English lullaby, 1784

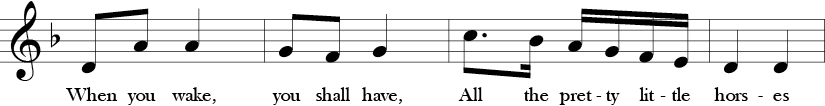

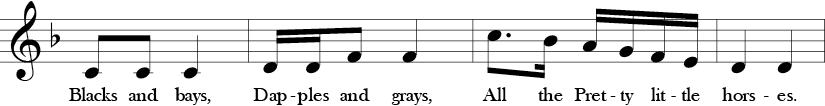

African American lullaby

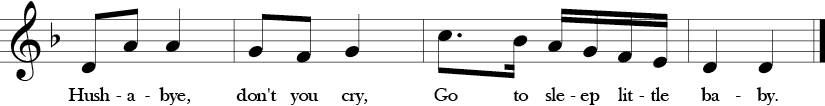

American lullaby song

Three- to five-year-olds are capable of singing more complicated songs, doing more complicated games and rhymes, and, of course, capable of more sophisticated listening. They can also understand some of the basic vocabulary and building blocks of music. It is appropriate to introduce a few concepts when performing songs and games with children, and also to experiment with these concepts, such as changing tempos and dynamics. Some vocabulary to use when pointing out these concept to younger children include:

For slightly older children, Feierabend (2001) identifies activities that help children develop spontaneous music ability and original music thinking under his “Arioso” category, as well as a detailed array of vocal- and motor-based experiences with music.

An 8-part Music Readiness Curriculum for 3–8 Year Old Children by John Feierabend. Copyright 2014 GIA Publications, Inc. 7404 S. Mason Ave., Chicago IL 60638 www.giamusic.com. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Singing/Tonal Activity Categories |

|

1. Pitch Exploration/Vocal Warm-up |

Discovering the sensation of the singing voice

|

2. Fragment Singing |

Developing independent singing

|

3. Simple Songs |

Developing independent singing and musical syntax

|

4. Arioso |

Developing original musical thinking

|

5. Song Tales |

Developing expressive sensitivity through listening

|

Movement Activities Categories |

|

6. Movement Exploration/Warm-up |

Developing expressive sensitivity through movement

|

7. Movement for Form and Expression |

Singing/speaking and moving with formal structure and expression

|

8. Beat Motion Activities |

Developing competencies in maintaining the beat in groups of two and three

|

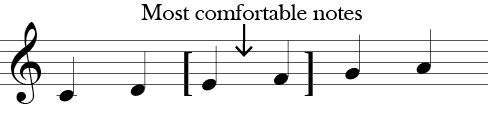

Preschoolers (three-, four-, and five-year-olds) have a range of six notes between a middle C and the A above it. Their most comfortable notes are in the middle between E and F.

The goal is to have them not sing too far below the staff or too low in their voices, and to not push or strain their voices too far above this range either. Singing should be light, in the child’s head voice, never forced or pushed, and beautiful music-making should be stressed.

Initially, children need to explore their voices to find out what they are capable of, and to start hearing that their voices do indeed have a range to them. It is very good for children to make light, airy, and smooth sounds in their head voice as they find their individual sound.

Begin with some vocal exploration with speech, just getting them to loosen up and find their high, light head voice.

I take my voice up high (start low, and slide voice up)

I bring my voice down low (Start high, and slide voice down)

I send my voice out into space (Cup hands around mouth and project)

I whisper all around, whisper, whisper (Whisper line and whisper to neighbors)

Bow wow, says the dog (medium voice)

Meow, meow says the cat (high voice)

Grunt, grunt says the hog (low voice)

Squeak, squeak says the rat (very high)

Have the children pretend their voice is an elevator sliding up and down between floors. They can accompany their vocal exploration with physical moving up and down as well, or the teacher may want to have a focal object like a puppet moving up and down that they can follow with their voice.

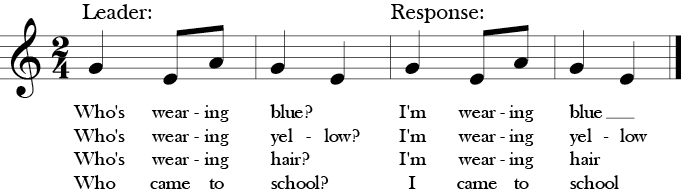

Begin with simple but interesting songs with small ranges. These songs can be varied and repeated, and help children sing accurately. “Who’s Wearing Blue” is an excellent warm-up or opening activity in a music class. What did the children wear? do? see? There are endless, creative opportunities to ask them about their lives in a few notes.

English traditional street cry, 1733

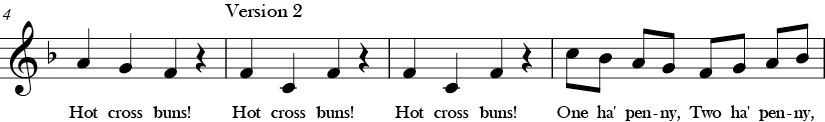

Traditional children’s song, 17th century

Children form a single line, holding on the waist of the child in front of them. The child at the front of the line is the snail’s head, who holds up and wiggles both index fingers on the forehead representing the snail’s eyestalks. The line shuffles around the room imitating the slow, fluid motions of a snail.

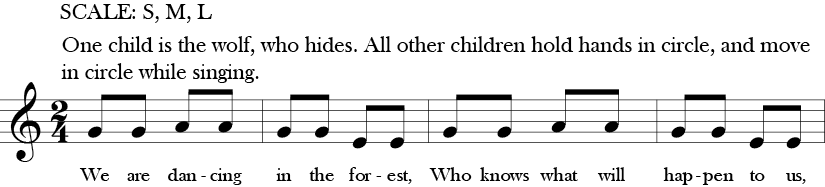

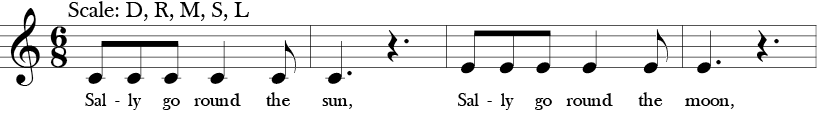

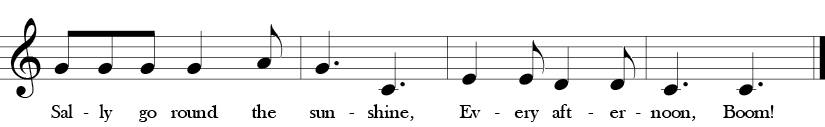

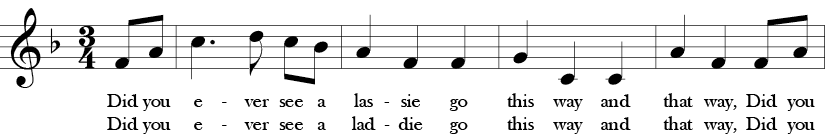

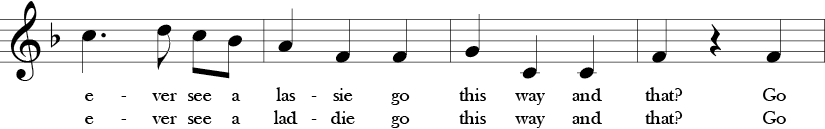

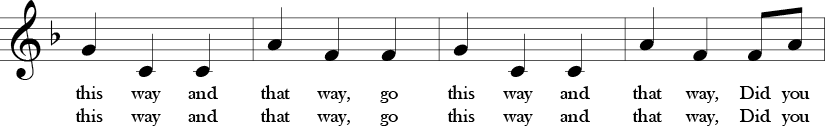

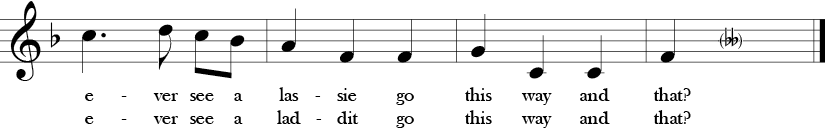

Traditional American circle game song

English nursery rhyme, 1765

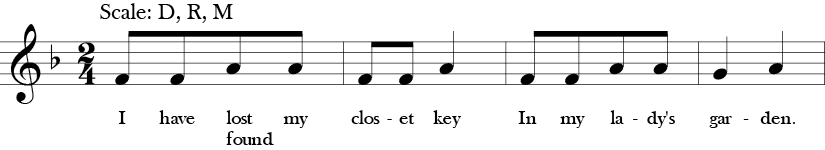

American folk song

Accompanying game for “I Have Lost my Closet Key”: Children sit in a circle. One child hides a key in their hand while another child walks around the circle trying to guess who has the key while all sing Verse 1. After finding the key, all sing Verse 2. That person then becomes “it” and another is chosen to hide the key.

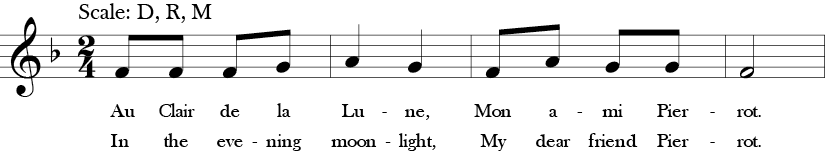

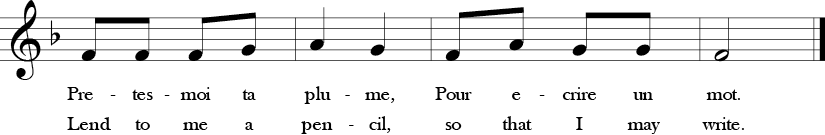

French folk song

English song attributed to 1665 Black Plague, but sources only go back to 19th century

Appalachian folk song

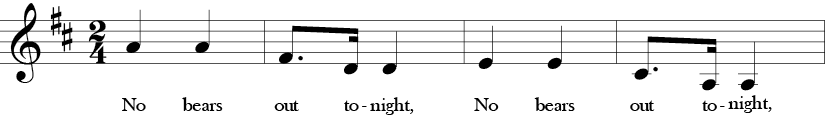

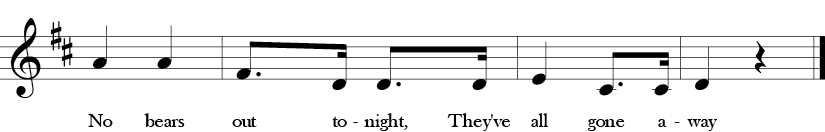

One child is the “bear” who hides while others count one o’ clock to midnight.

Children search for the bear, then run back to “home” when the bear is found.

English nursery rhyme, 1840s

High/Low Pitches: You or a child plays a low instrument (drum, bass xylophone, etc.) and children respond by moving in low space. Then try the same for high-pitched instruments (triangle, tambourine, etc.), having them move through high space.

Fast/Slow Tempo and Loud/Soft Dynamics Game: Similar to above, play instruments in different tempos and dynamics. Switch and mix them up (fast and loud, soft and slow, fast and soft, slow and loud), and if the child doesn’t switch, he or she is out.

Contrasting Timbres: Assign a different movement to different timbres. For example, a wood block corresponds to a hop, a xylophone glissando is a leap, a shaker means to shake. Create an orchestra with half of the class playing and the other half responding. For more advanced children, create a choreographed and composed piece from the game.

Musical Simon Says: Review concepts learned such as loud/soft, high/low, or fast/slow. Simon says yell loud, Simon says whisper, Simon says sing high, Simon says groan low, etc.

Poetry and rhymes are among the most basic forms of human expression, and both children and adults use poetry, rhymes, and games to tell stories, remember history, fantasize, dream, and play. For young children, the rhyme is magical as they first encounter the powerful sound of rhyming words. Words create rhythmic patterns that captivate a child’s attention. The natural rhythms inherent in rhyming can become the basis for exploration, improvisation, vocalizations, and instrumental creativity.

Rhymes with actions, in particular, are enjoyable to children because children live through all of their senses and their whole body. Adding movement helps reinforce the linguistic content of the rhyme or song. Movement and rhymes build cognitive abilities in terms of sequencing physical and linguistic activity, imitation, and internalization.

There are many types of movement to add to rhymes and games. There are narrative movements, which are mimetic actions that help to illustrate certain words and tell the story (e.g., “I’m a Little Teapot”); abstract movements, which do not carry any specific linguistic meaning, such as waving arms or jumping; and rhythmic movements, which can either emphasize the beat of the rhyme or the rhythm of the text, such as clapping or body percussion.

Narrative Movements: It is easy to add narrative movements to most children’s rhymes as these poems often tell some type of story. Consider the rhyme “I’m a Little Ducky.” Adding swimming and flapping motions would be an obvious activity to add. Narrative motions not only bring the story to life, but also significantly help children to remember the words to a rhyme or song.

I’m a little ducky swimming in the water

I’m a little ducky doing what I oughter

Took a bite of a lily pad

Flapped my wings and said, “I’m glad”

I’m a little ducky swimming in the water

Flap, flap, flap

Abstract Motions and Rhythmic Motions: Almost any non-locomotive or even some locomotive motions would work here. Abstract motions can easily be rhythmic as well (e.g., swaying to the beat, nodding the head to the beat, tapping the rhythm of the words or beat, etc.).

Walking to the Beat: While a seemingly simple-sounding exercise, walking to the beat requires a physical awareness and near-constant mental and physical adjustment to the walking stride in order to fit the beat and tempo of the rhyme.

Example: Take any standard, well-known nursery rhyme. Walk to the beat while saying the rhyme. End precisely on the last beat of the rhyme and freeze!

Advanced: This game can be further developed for older or more advanced children. Once they are walking to a steady beat and stopping precisely on the last beat, have children drop the recitation of the rhyme, and just walk the beat. See if they can all still stop on the last beat! This helps students internalize the beat and phrases of the song.

Pass the Beat: Begin with a simple rhyme or song. While sitting in a circle, have students pass a beanbag around the circle on the beat. If the child misses, they are “out” or “in the soup” in the middle of the circle.

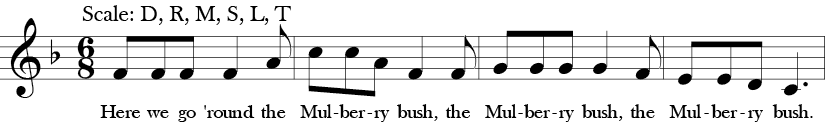

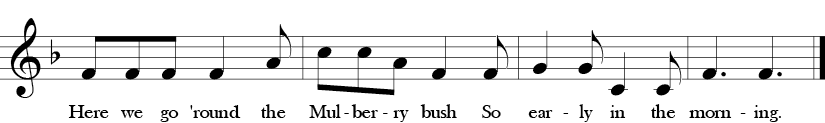

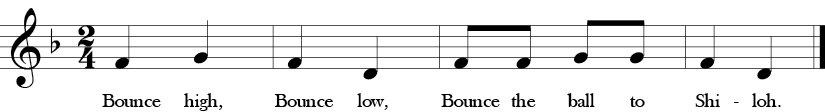

Bouncing Beat: Another game is to bounce a ball to the beat of a simple song such as “Bounce High.” This is a little more challenging because they have to keep control of their bodies, voices, and a ball.

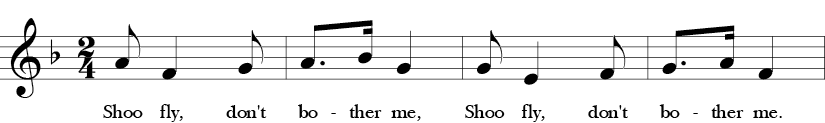

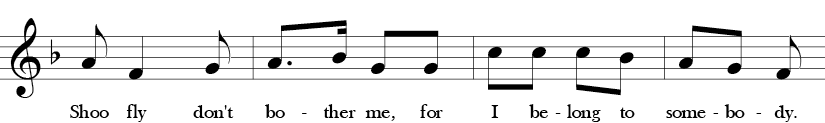

American folk song, 1863

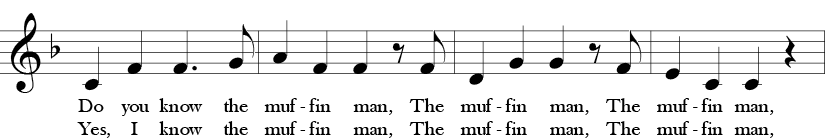

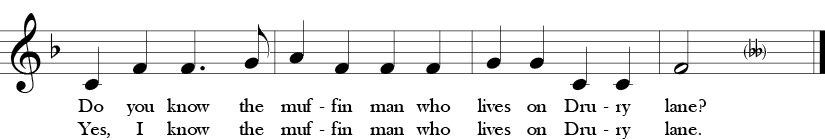

English folk song, 1820

American folk song, late 19th century

Deedle, deedle dumpling, my son John

Went to bed with his stockings on

One shoe off and one shoe on

Deedle, deedle dumpling, my son John

Oliver Twist, Twist, Twist

Can’t do this, this, this

Touch his nose, nose, nose

Touch his toes, toes, toes

And around he goes, goes, goes

Rub, rub, rub

________’s in the tub

Rub her/him dry

Hang her high

Rub, rub, rub

Jingle, jingle, jingle jive

Move until you count to five

1, 2, 3, 4, 5

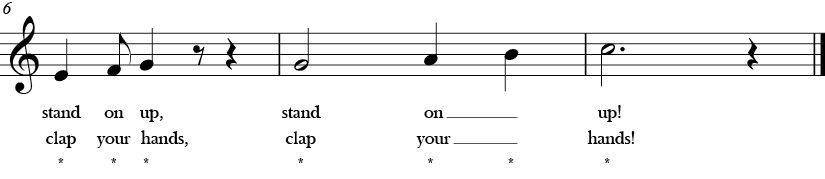

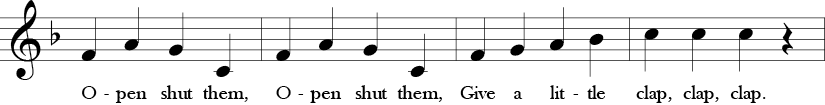

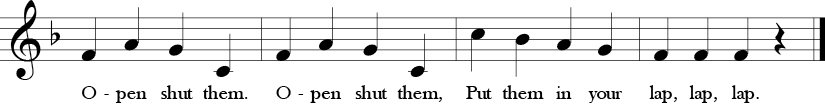

This is an action game song where the lyrics are imitated through movement using simple actions in both hands.

Open, shut them, Open, shut them, (open and shut both hands)

Give a little clap, clap, clap (clap on each “clap”)

Open, shut them, Open, shut them, (open and shut both hands)

Put them in you lap, lap, lap (tap open hands on thighs)

Creep them, creep them, creep them, creep them, (crawl hands up to chin)

Right up to your chin, chin, chin (tap on each “chin”)

Open wide your little mouth (open mouth)

But do not put them in, in, in (tap on each “chin” again)

Although we might not have thought of it, children’s linguistic development is related to their musical development. Research shows a direct correlation between the development of children’s speech and their musical/singing ability, with music skills correlating significantly with both phonological awareness and reading development (Anvari et al., 2002).

While teachers of preschool children may have a sense of the linguistic milestones for children, they are less aware of the musical milestones. Since music and language development have a high correlation in terms of development, it is helpful to know what activities children are developmentally ready for musically, and when are they ready for them. For example, most four- and even five-year-olds are not yet able to play a steady beat on an instrument. Expecting them to will only frustrate both the children and yourself. The following chart indicates musical developmental ability by age, and will guide you in introducing musical skills and material that children are developmentally ready for.

Age |

Musical Behaviors |

Appropriate Activities |

Limitations |

0–1 year old (Infants) |

Enjoy hearing:

|

Enjoy:

|

Cannot use language or sing |

1–2 years old (Toddlers) |

|

|

Cannot sing “in tune” but can maintain melodic contour Developmental Issues: “Centering” (pre-operational stage) can fix a child’s attention on one perceptual feature. Difficulty seeing the larger transformational picture of some activities as attention is diverted by one feature. |

3-year-olds |

Enjoy:

|

|

Developmental Issues:

|

4-year-olds |

|

|

|

4–5-year-olds |

Able to classify sounds as:

|

Prefer:

|

|

Activity 8B Try this Based on the chart above, answer the following in terms of what age is appropriate for each activity. 1. Analyzing/hearing the different sections of a song. 2. Responding vocally using different tones and inflections. 3. Singing the song “I’m a Nut.” 4. Echoing/responding to short, clapped rhythms. 5. Playing a steady beat on the xylophone or other percussion instrument. 6. Seeing abstract images and performing them either on voice or instruments. |

Anvari, S., Trainor, L., Woodside, J., & Levy, A. (2002). Relations among musical skills, phonological processing, and early reading ability in preschool children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 83(2), 111–130.

Chen-Hafteck, L. (1997). Music and language development in early childhood: Integrating past research in the two domains In Early Child Development and Care 130 (1): 85-97.

Deliège, I. and Sloboda, J. (Eds.). (1996). Musical beginnings: Origins and development of musical competence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feierabend, J. (2001). First steps in classical music: Keeping the beat. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Feierabend, J. (2006). First steps in music for preschool and beyond : The curriculum. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Gordon, E. E. (2007). Learning sequences in music: A contemporary music learning theory. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Gordon, E. E. (2007). Learning sequences in music: A contemporary music learning

theory: Study guide. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Gordon, E. E. (2007). Lecture cds for learning sequences in music: A contemporary music learning theory. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Gordon, E. (2000). Jump right in: Grade 1 teacher’s guide—The general music series (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Haroutounian, J. (2002). Kindling the spark: Recognizing and developing musical talent. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jensen, E. (1998). Teaching with the brain in mind. Alexandria, VA: ASCD Publisher.

Jordan-DeCarbo, J., and Galliford, J. (2011). The effect of an age-appropriate music curriculum on motor and linguistic and nonlinguistic skills of children three to five years of age. In S. Burton & C. Taggart (Eds.), Learning from young children: Research in early childhood music (pp. 211–230). Lanham, MD: MENC and Rowman Littlefield.

Moore, R. S. (1991). Comparison of children’s and adults’ vocal ranges and preferred tessituras in singing familiar songs. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education, Winter, 13–22.

Reynolds, A., Bolton, B., Taggert, C., Valerio, W., & Gordon, E. (1998). Music play: The early childhood music curriculum guide. Chicago, IL: GIA Publications.

Suzuki, S., and Nagata, M. L. (1981). Ability development from age zero. Athens, OH: Suzuki Method International.

Turner, M. E. (2008). Listen, move, think: Communicating through the languages of music and creative movement. Retrieved from http://www.listenmovethink.com/#intro

abstract movements: movements do not carry any specific linguistic meaning, such as waving arms or jumping

articulation: the approach to playing a note and style of playing in terms of its smoothness, detachment, accents, etc.

dynamics: how loud or soft the music is

meter: meter determines where the stresses in music are, or how music stresses are grouped. A triple meter, for example, will have groups of 3 with a stress on the first beat of the group. A duple meter will have groups of 2 with a stress on the first beat of the group.

narrative movements: mimetic actions that help to illustrate certain words and tell the story (e.g., “I’m a Little Teapot”)

pitch: how high or low a note is

rhythmic movements: movements that can either emphasize the beat of the rhyme or the rhythm of the text, such as clapping or body percussion

tempo: how fast or slow the music is played

timbre: the quality of sound

Library Info and Research Help | reflibrarian@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4215

Loans or Fines | circ@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4222

475 Grand Concourse (A Building), Room 308, Bronx, NY 10451