Click on the printer icon at the bottom of the screen

![]()

Make sure that your printout includes all content from the page. If it doesn't, try opening this guide in a different browser and printing from there (sometimes Internet Explorer works better, sometimes Chrome, sometimes Firefox, etc.).

If the above process produces printouts with errors or overlapping text or images, try this method:

Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders by Deanna M. Barch is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

Schizophrenia and the other psychotic disorders are some of the most impairing forms of psychopathology, frequently associated with a profound negative effect on the individual’s educational, occupational, and social function. Sadly, these disorders often manifest right at time of the transition from adolescence to adulthood, just as young people should be evolving into independent young adults. The spectrum of psychotic disorders includes schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, schizophreniform disorder, brief psychotic disorder, as well as psychosis associated with substance use or medical conditions. In this module, we summarize the primary clinical features of these disorders, describe the known cognitive and neurobiological changes associated with schizophrenia, describe potential risk factors and/or causes for the development of schizophrenia, and describe currently available treatments for schizophrenia.

Most of you have probably had the experience of walking down the street in a city and seeing a person you thought was acting oddly. They may have been dressed in an unusual way, perhaps disheveled or wearing an unusual collection of clothes, makeup, or jewelry that did not seem to fit any particular group or subculture. They may have been talking to themselves or yelling at someone you could not see. If you tried to speak to them, they may have been difficult to follow or understand, or they may have acted paranoid or started telling a bizarre story about the people who were plotting against them. If so, chances are that you have encountered an individual with schizophrenia or another type of psychotic disorder. If you have watched the movie A Beautiful Mind or The Fisher King, you have also seen a portrayal of someone thought to have schizophrenia. Sadly, a few of the individuals who have committed some of the recently highly publicized mass murders may have had schizophrenia, though most people who commit such crimes do not have schizophrenia. It is also likely that you have met people with schizophrenia without ever knowing it, as they may suffer in silence or stay isolated to protect themselves from the horrors they see, hear, or believe are operating in the outside world. As these examples begin to illustrate, psychotic disorders involve many different types of symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech and behavior, abnormal motor behavior (including catatonia), and negative symptoms such anhedonia/amotivation and blunted affect/reduced speech.

Delusions are false beliefs that are often fixed, hard to change even when the person is presented with conflicting information, and are often culturally influenced in their content (e.g., delusions involving Jesus in Judeo-Christian cultures, delusions involving Allah in Muslim cultures). They can be terrifying for the person, who may remain convinced that they are true even when loved ones and friends present them with clear information that they cannot be true. There are many different types or themes to delusions.

Figure 1: Under Surveillance: Abstract groups like the police or the government are commonly the focus of a schizophrenic's persecutory delusions. [Image: Thomas Hawk, https://goo.gl/qsrqiR, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/VnKlK8]

The most common delusions are persecutory and involve the belief that individuals or groups are trying to hurt, harm, or plot against the person in some way. These can be people that the person knows (people at work, the neighbors, family members), or more abstract groups (the FBI, the CIA, aliens, etc.). Other types of delusions include grandiose delusions, where the person believes that they have some special power or ability (e.g., I am the new Buddha, I am a rock star); referential delusions, where the person believes that events or objects in the environment have special meaning for them (e.g., that song on the radio is being played specifically for me); or other types of delusions where the person may believe that others are controlling their thoughts and actions, their thoughts are being broadcast aloud, or that others can read their mind (or they can read other people’s minds).

When you see a person on the street talking to themselves or shouting at other people, they are experiencing hallucinations. These are perceptual experiences that occur even when there is no stimulus in the outside world generating the experiences. They can be auditory, visual, olfactory (smell), gustatory (taste), or somatic (touch). The most common hallucinations in psychosis (at least in adults) are auditory, and can involve one or more voices talking about the person, commenting on the person’s behavior, or giving them orders. The content of the hallucinations is frequently negative (“you are a loser,” “that drawing is stupid,” “you should go kill yourself”) and can be the voice of someone the person knows or a complete stranger. Sometimes the voices sound as if they are coming from outside the person’s head. Other times the voices seem to be coming from inside the person’s head, but are not experienced the same as the person’s inner thoughts or inner speech.

Talking to someone with schizophrenia is sometimes difficult, as their speech may be difficult to follow, either because their answers do not clearly flow from your questions, or because one sentence does not logically follow from another. This is referred to as disorganized speech, and it can be present even when the person is writing. Disorganized behavior can include odd dress, odd makeup (e.g., lipstick outlining a mouth for 1 inch), or unusual rituals (e.g., repetitive hand gestures). Abnormal motor behavior can include catatonia, which refers to a variety of behaviors that seem to reflect a reduction in responsiveness to the external environment. This can include holding unusual postures for long periods of time, failing to respond to verbal or motor prompts from another person, or excessive and seemingly purposeless motor activity.

Some of the most debilitating symptoms of schizophrenia are difficult for others to see. These include what people refer to as “negative symptoms” or the absence of certain things we typically expect most people to have. For example, anhedonia or amotivation reflect a lack of apparent interest in or drive to engage in social or recreational activities. These symptoms can manifest as a great amount of time spent in physical immobility. Importantly, anhedonia and amotivation do not seem to reflect a lack of enjoyment in pleasurable activities or events (Cohen & Minor, 2010; Kring & Moran, 2008; Llerena, Strauss, & Cohen, 2012) but rather a reduced drive or ability to take the steps necessary to obtain the potentially positive outcomes (Barch & Dowd, 2010). Flat affect and reduced speech (alogia) reflect a lack of showing emotions through facial expressions, gestures, and speech intonation, as well as a reduced amount of speech and increased pause frequency and duration.

In many ways, the types of symptoms associated with psychosis are the most difficult for us to understand, as they may seem far outside the range of our normal experiences. Unlike depression or anxiety, many of us may not have had experiences that we think of as on the same continuum as psychosis. However, just like many of the other forms of psychopathology described in this book, the types of psychotic symptoms that characterize disorders like schizophrenia are on a continuum with “normal” mental experiences. For example, work by Jim van Os in the Netherlands has shown that a surprisingly large percentage of the general population (10%+) experience psychotic-like symptoms, though many fewer have multiple experiences and most will not continue to experience these symptoms in the long run (Verdoux & van Os, 2002). Similarly, work in a general population of adolescents and young adults in Kenya has also shown that a relatively high percentage of individuals experience one or more psychotic-like experiences (~19%) at some point in their lives (Mamah et al., 2012; Ndetei et al., 2012), though again most will not go on to develop a full-blown psychotic disorder.

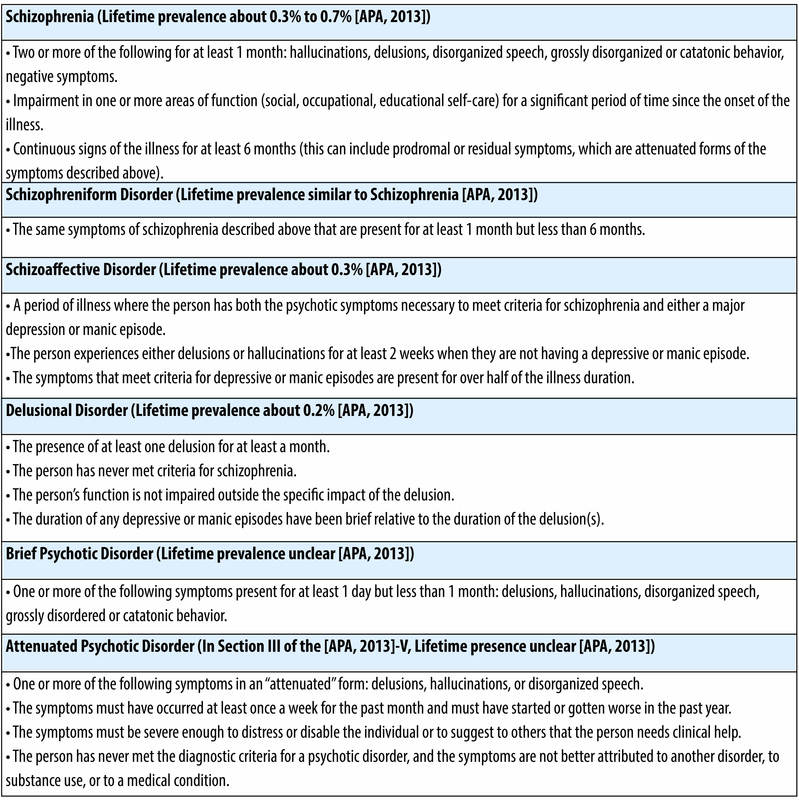

Schizophrenia is the primary disorder that comes to mind when we discuss “psychotic” disorders (see Table 1 for diagnostic criteria), though there are a number of other disorders that share one or more features with schizophrenia. In the remainder of this module, we will use the terms “psychosis” and “schizophrenia” somewhat interchangeably, given that most of the research has focused on schizophrenia. In addition to schizophrenia (see Table 1), other psychotic disorders include schizophreniform disorder (a briefer version of schizophrenia), schizoaffective disorder (a mixture of psychosis and depression/mania symptoms), delusional disorder (the experience of only delusions), and brief psychotic disorder (psychotic symptoms that last only a few days or weeks).

As described above, when we think of the core symptoms of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia, we think of people who hear voices, see visions, and have false beliefs about reality (i.e., delusions). However, problems in cognitive function are also a critical aspect of psychotic disorders and of schizophrenia in particular. This emphasis on cognition in schizophrenia is in part due to the growing body of research suggesting that cognitive problems in schizophrenia are a major source of disability and loss of functional capacity (Green, 2006; Nuechterlein et al., 2011). The cognitive deficits that are present in schizophrenia are widespread and can include problems with episodic memory (the ability to learn and retrieve new information or episodes in one’s life), working memory (the ability to maintain information over a short period of time, such as 30 seconds), and other tasks that require one to “control” or regulate one’s behavior (Barch & Ceaser, 2012; Bora, Yucel, & Pantelis, 2009a; Fioravanti, Carlone, Vitale, Cinti, & Clare, 2005; Forbes, Carrick, McIntosh, & Lawrie, 2009; Mesholam-Gately, Giuliano, Goff, Faraone, & Seidman, 2009). Individuals with schizophrenia also have difficulty with what is referred to as “processing speed” and are frequently slower than healthy individuals on almost all tasks. Importantly, these cognitive deficits are present prior to the onset of the illness (Fusar-Poli et al., 2007) and are also present, albeit in a milder form, in the first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia (Snitz, Macdonald, & Carter, 2006). This suggests that cognitive impairments in schizophrenia reflect part of the risk for the development of psychosis, rather than being an outcome of developing psychosis. Further, people with schizophrenia who have more severe cognitive problems also tend to have more severe negative symptoms and more disorganized speech and behavior (Barch, Carter, & Cohen, 2003; Barch et al., 1999; Dominguez Mde, Viechtbauer, Simons, van Os, & Krabbendam, 2009; Ventura, Hellemann, Thames, Koellner, & Nuechterlein, 2009; Ventura, Thames, Wood, Guzik, & Hellemann, 2010). In addition, people with more cognitive problems have worse function in everyday life (Bowie et al., 2008; Bowie, Reichenberg, Patterson, Heaton, & Harvey, 2006; Fett et al., 2011).

Figure 3: Some with schizophrenia suffer from difficulty with social cognition. They may not be able to detect the meaning of facial expressions or other subtle cues that most other people rely on to navigate the social world. [Image: Ralph Buckley, https://goo.gl/KuBzsD, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://goo.gl/i4GXf5]

Some people with schizophrenia also show deficits in what is referred to as social cognition, though it is not clear whether such problems are separate from the cognitive problems described above or the result of them (Hoe, Nakagami, Green, & Brekke, 2012; Kerr & Neale, 1993; van Hooren et al., 2008). This includes problems with the recognition of emotional expressions on the faces of other individuals (Kohler, Walker, Martin, Healey, & Moberg, 2010) and problems inferring the intentions of other people (theory of mind) (Bora, Yucel, & Pantelis, 2009b). Individuals with schizophrenia who have more problems with social cognition also tend to have more negative and disorganized symptoms (Ventura, Wood, & Hellemann, 2011), as well as worse community function (Fett et al., 2011).

The advent of neuroimaging techniques such as structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography opened up the ability to try to understand the brain mechanisms of the symptoms of schizophrenia as well as the cognitive impairments found in psychosis. For example, a number of studies have suggested that delusions in psychosis may be associated with problems in “salience” detection mechanisms supported by the ventral striatum (Jensen & Kapur, 2009; Jensen et al., 2008; Kapur, 2003; Kapur, Mizrahi, & Li, 2005; Murray et al., 2008) and the anterior prefrontal cortex (Corlett et al., 2006; Corlett, Honey, & Fletcher, 2007; Corlett, Murray, et al., 2007a, 2007b). These are regions of the brain that normally increase their activity when something important (aka “salient”) happens in the environment. If these brain regions misfire, it may lead individuals with psychosis to mistakenly attribute importance to irrelevant or unconnected events. Further, there is good evidence that problems in working memory and cognitive control in schizophrenia are related to problems in the function of a region of the brain called the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (Minzenberg, Laird, Thelen, Carter, & Glahn, 2009; Ragland et al., 2009). These problems include changes in how the DLPFC works when people are doing working-memory or cognitive-control tasks, and problems with how this brain region is connected to other brain regions important for working memory and cognitive control, including the posterior parietal cortex (e.g., Karlsgodt et al., 2008; J. J. Kim et al., 2003; Schlosser et al., 2003), the anterior cingulate (Repovs & Barch, 2012), and temporal cortex (e.g., Fletcher et al., 1995; Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2001). In terms of understanding episodic memory problems in schizophrenia, many researchers have focused on medial temporal lobe deficits, with a specific focus on the hippocampus (e.g., Heckers & Konradi, 2010). This is because there is much data from humans and animals showing that the hippocampus is important for the creation of new memories (Squire, 1992). However, it has become increasingly clear that problems with the DLPFC also make important contributions to episodic memory deficits in schizophrenia (Ragland et al., 2009), probably because this part of the brain is important for controlling our use of memory.

In addition to problems with regions such as the DLFPC and medial temporal lobes in schizophrenia described above, magnitude resonance neuroimaging studies have also identified changes in cellular architecture, white matter connectivity, and gray matter volume in a variety of regions that include the prefrontal and temporal cortices (Bora et al., 2011). People with schizophrenia also show reduced overall brain volume, and reductions in brain volume as people get older may be larger in those with schizophrenia than in healthy people (Olabi et al., 2011). Taking antipsychotic medications or taking drugs such as marijuana, alcohol, and tobacco may cause some of these structural changes. However, these structural changes are not completely explained by medications or substance use alone. Further, both functional and structural brain changes are seen, again to a milder degree, in the first-degree relatives of people with schizophrenia (Boos, Aleman, Cahn, Pol, & Kahn, 2007; Brans et al., 2008; Fusar-Poli et al., 2007; MacDonald, Thermenos, Barch, & Seidman, 2009). This again suggests that that neural changes associated with schizophrenia are related to a genetic risk for this illness.

It is clear that there are important genetic contributions to the likelihood that someone will develop schizophrenia, with consistent evidence from family, twin, and adoption studies. (Sullivan, Kendler, & Neale, 2003). However, there is no “schizophrenia gene” and it is likely that the genetic risk for schizophrenia reflects the summation of many different genes that each contribute something to the likelihood of developing psychosis (Gottesman & Shields, 1967; Owen, Craddock, & O'Donovan, 2010). Further, schizophrenia is a very heterogeneous disorder, which means that two different people with “schizophrenia” may each have very different symptoms (e.g., one has hallucinations and delusions, the other has disorganized speech and negative symptoms). This makes it even more challenging to identify specific genes associated with risk for psychosis. Importantly, many studies also now suggest that at least some of the genes potentially associated with schizophrenia are also associated with other mental health conditions, including bipolar disorder, depression, and autism (Gejman, Sanders, & Kendler, 2011; Y. Kim, Zerwas, Trace, & Sullivan, 2011; Owen et al., 2010; Rutter, Kim-Cohen, & Maughan, 2006).

Figure 4: There are a number of genetic and environmental risk factors associated with higher likelihood of developing schizophrenia including older fathers, complications during pregnancy/delivery, family history of schizophrenia, and growing up in an urban environment. [Image: CC0 Public Domain]

There are also a number of environmental factors that are associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia. For example, problems during pregnancy such as increased stress, infection, malnutrition, and/or diabetes have been associated with increased risk of schizophrenia. In addition, complications that occur at the time of birth and which cause hypoxia (lack of oxygen) are also associated with an increased risk for developing schizophrenia (M. Cannon, Jones, & Murray, 2002; Miller et al., 2011). Children born to older fathers are also at a somewhat increased risk of developing schizophrenia. Further, using cannabis increases risk for developing psychosis, especially if you have other risk factors (Casadio, Fernandes, Murray, & Di Forti, 2011; Luzi, Morrison, Powell, di Forti, & Murray, 2008). The likelihood of developing schizophrenia is also higher for kids who grow up in urban settings (March et al., 2008) and for some minority ethnic groups (Bourque, van der Ven, & Malla, 2011). Both of these factors may reflect higher social and environmental stress in these settings. Unfortunately, none of these risk factors is specific enough to be particularly useful in a clinical setting, and most people with these “risk” factors do not develop schizophrenia. However, together they are beginning to give us clues as the neurodevelopmental factors that may lead someone to be at an increased risk for developing this disease.

An important research area on risk for psychosis has been work with individuals who may be at “clinical high risk.” These are individuals who are showing attenuated (milder) symptoms of psychosis that have developed recently and who are experiencing some distress or disability associated with these symptoms. When people with these types of symptoms are followed over time, about 35% of them develop a psychotic disorder (T. D. Cannon et al., 2008), most frequently schizophrenia (Fusar-Poli, McGuire, & Borgwardt, 2012). In order to identify these individuals, a new category of diagnosis, called “Attenuated Psychotic Syndrome,” was added to Section III (the section for disorders in need of further study) of the DSM-5 (see Table 1 for symptoms) (APA, 2013). However, adding this diagnostic category to the DSM-5 created a good deal of controversy (Batstra & Frances, 2012; Fusar-Poli & Yung, 2012). Many scientists and clinicians have been worried that including “risk” states in the DSM-5 would create mental disorders where none exist, that these individuals are often already seeking treatment for other problems, and that it is not clear that we have good treatments to stop these individuals from developing to psychosis. However, the counterarguments have been that there is evidence that individuals with high-risk symptoms develop psychosis at a much higher rate than individuals with other types of psychiatric symptoms, and that the inclusion of Attenuated Psychotic Syndrome in Section III will spur important research that might have clinical benefits. Further, there is some evidence that non-invasive treatments such as omega-3 fatty acids and intensive family intervention may help reduce the development of full-blown psychosis (Preti & Cella, 2010) in people who have high-risk symptoms.

The currently available treatments for schizophrenia leave much to be desired, and the search for more effective treatments for both the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., hallucinations and delusions) as well as cognitive deficits and negative symptoms is a highly active area of research. The first line of treatment for schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders is the use of antipsychotic medications. There are two primary types of antipsychotic medications, referred to as “typical” and “atypical.” The fact that “typical” antipsychotics helped some symptoms of schizophrenia was discovered serendipitously more than 60 years ago (Carpenter & Davis, 2012; Lopez-Munoz et al., 2005). These are drugs that all share a common feature of being a strong block of the D2 type dopamine receptor. Although these drugs can help reduce hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized speech, they do little to improve cognitive deficits or negative symptoms and can be associated with distressing motor side effects. The newer generation of antipsychotics is referred to as “atypical” antipsychotics. These drugs have more mixed mechanisms of action in terms of the receptor types that they influence, though most of them also influence D2 receptors. These newer antipsychotics are not necessarily more helpful for schizophrenia but have fewer motor side effects. However, many of the atypical antipsychotics are associated with side effects referred to as the “metabolic syndrome,” which includes weight gain and increased risk for cardiovascular illness, Type-2 diabetes, and mortality (Lieberman et al., 2005).

The evidence that cognitive deficits also contribute to functional impairment in schizophrenia has led to an increased search for treatments that might enhance cognitive function in schizophrenia. Unfortunately, as of yet, there are no pharmacological treatments that work consistently to improve cognition in schizophrenia, though many new types of drugs are currently under exploration. However, there is a type of psychological intervention, referred to as cognitive remediation, which has shown some evidence of helping cognition and function in schizophrenia. In particular, a version of this treatment called Cognitive Enhancement Therapy (CET) has been shown to improve cognition, functional outcome, social cognition, and to protect against gray matter loss (Eack et al., 2009; Eack, Greenwald, Hogarty, & Keshavan, 2010; Eack et al., 2010; Eack, Pogue-Geile, Greenwald, Hogarty, & Keshavan, 2010; Hogarty, Greenwald, & Eack, 2006) in young individuals with schizophrenia. The development of new treatments such as Cognitive Enhancement Therapy provides some hope that we will be able to develop new and better approaches to improving the lives of individuals with this serious mental health condition and potentially even prevent it some day.

Book: Ben Behind His Voices: One family’s journal from the chaos of schizophrenia to hope (2011). Randye Kaye. Rowman and Littlefield.

Book: Conquering Schizophrenia: A father, his son, and a medical breakthrough (1997). Peter Wyden. Knopf.

Book: Henry’s Demons: Living with schizophrenia, a father and son’s story (2011). Henry and Patrick Cockburn. Scribner Macmillan.

Book: My Mother’s Keeper: A daughter’s memoir of growing up in the shadow of schizophrenia (1997). Tara Elgin Holley. William Morrow Co.

Book: Recovered, Not Cured: A journey through schizophrenia (2005). Richard McLean. Allen and Unwin.

Book: The Center Cannot Hold: My journey through madness (2008). Elyn R. Saks. Hyperion.

Book: The Quiet Room: A journal out of the torment of madness (1996). Lori Schiller. Grand Central Publishing.

Book: Welcome Silence: My triumph over schizophrenia (2003). Carol North. CSS Publishing.

Web: National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. This is an excellent site for learning more about advocacy for individuals with major mental illnesses such as schizophrenia.

Web: National Institute of Mental Health. This website has information on NIMH-funded schizophrenia research.

Web: Schizophrenia Research Forum. This is an excellent website that contains a broad array of information about current research on schizophrenia.

This guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Library Info and Research Help | reflibrarian@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4215

Loans or Fines | circ@hostos.cuny.edu (718) 518-4222

475 Grand Concourse (A Building), Room 308, Bronx, NY 10451